Authentication

170x Tipe PDF Ukuran file 0.76 MB Source: DeLanda

Deleuze: History and Science.

1

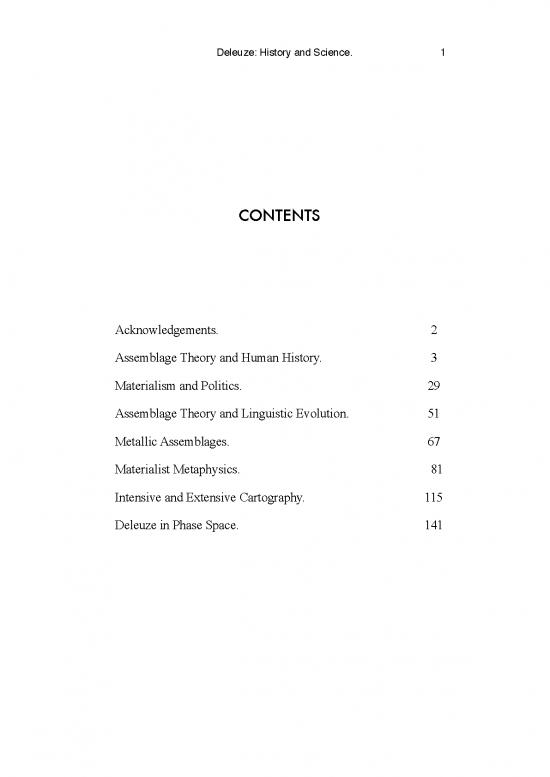

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements. 2

Assemblage Theory and Human History. 3

Materialism and Politics. 29

Assemblage Theory and Linguistic Evolution. 51

Metallic Assemblages. 67

Materialist Metaphysics. 81

Intensive and Extensive Cartography. 115

Deleuze in Phase Space. 141

2 Deleuze: History and Science.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.

Some of the essays that make up this book are published here

for the first time, but some have appeared in other publications in

modified form. The publishers acknowledge that some material has

been previously published in the following collections:

Deleuzian Social Ontology and Assemblage Theory. In Deleuze and the

Social. Edited by Martin Fuglsang and Bent Meier Sørensen.

(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006.)

Deleuze, Materialism, and Politics. In Deleuze and Politics. Edited by

Ian Buchanan and Nicholas Thoburn. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press, 2008.)

Molar Entities and Molecular Populations in History. In Deleuze and

History. Edited by Jeffrey Bell and Claire Colebrook. (Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 2009.)

Deleuze in Phase Space. In Virtual Mathematics. Edited by Simon

Duffy. (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2006.)

Deleuze: History and Science.

3

Assemblages and Human History.

We no longer believe in a primordial totality that once

existed, or in a final totality that awaits us at some future date. We no

longer believe in the dull gray outlines of a dreary, colorless dialectic of

evolution, aimed at forming a harmonious whole out of heterogeneous

bits by rounding off their rough edges. We believe only in totalities that

are peripheral. And if we discover such a totality alongside various

separate parts, it is a whole of these particular parts but does not totalize

them; it is a unity of all those particular parts but does not unify them;

rather it is added to them as a new part fabricated separately.

1

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. The Anti-Oedipus.

A crucial question confronting any serious attempt to

think about human history is the nature of the historical actors

that are considered legitimate in a given philosophy. One can, of

course, include only human beings as actors, either as rational

decision-makers (as in micro-economics) or as

phenomenological subjects (as in micro-sociology). But if we

wish to go beyond this we need a proper conceptualization of

social wholes. The very first step in this task is to devise a means

to block micro-reductionism, a step usually achieved by the

concept of emergent properties, properties of a whole that are

not present in its parts: if a given social whole has properties that

emerge from the interactions between its parts, its reduction to a

mere aggregate of many rational decision makers or many

phenomenological experiences is effectively blocked. But this

leaves open the possibility of macro-reductionism, as when one

rejects the rational actors of micro-economics in favor of society

as a whole, a society that fully determines the nature of its

members. Blocking macro-reductionism demands a second

concept, the concept of relations of exteriority between parts.

Unlike wholes in which “being part of this whole” is a defining

characteristic of the parts, that is, wholes in which the parts

cannot subsist independently of the relations they have with each

other (relations of interiority) we need to conceive of emergent

4 Deleuze: History and Science.

wholes in which the parts retain a relative autonomy, so that they

can be detached from one whole and plugged into another one

entering into new interactions.

With these two concepts we can define social wholes,

like interpersonal networks or institutional organizations, that

cannot be reduced to the persons that compose them, and that, at

the same time, do not reduce those persons to the whole, fusing

them into a totality in which their individuality is lost. Take for

example the tightly-knit communities that inhabit small towns or

ethnic neighborhoods in large cities. In these communities an

important emergent property is the degree to which their

members are linked together. One way of examining this

property is to study networks of relations, counting the number

of direct and indirect links per person, and studying their

connectivity. A crucial property of these networks is their

density, an emergent property that may be roughly defined by

the degree to which the friends of the friends of any given

member (that is, his or her indirect links) know the indirect links

of others. Or to put it still more simply, by the degree to which

everyone knows everyone else. In a dense network word of

mouth travels fast, particularly when the content of the gossip is

the violation of a local norm: an unreciprocated favor, an unpaid

bet, an unfulfilled promise. This implies that the community as a

whole can act as a device for the storage of personal reputations

and, via simple behavioral punishments like ridicule or

ostracism, as an enforcement mechanism.

The property of density, and the capacity to store

reputations and enforce norms, are non-reducible properties and

capacities of the community as a whole, but neither involves

thinking of it as a seamless totality in which the members’

personal identity is created by the community. A similar point

applies to institutional organizations. Many organizations are

characterized by the possession of an authority structure in

which rights and obligations are distributed asymmetrically in a

hierarchical way. But the exercise of authority must be backed

by legitimacy if enforcement costs are to be kept within bounds.

Legitimacy is an emergent property of the entire organization

even if it depends for its existence on personal beliefs about its

source: a legitimizing tradition, a set of written regulations, or

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.