180x Filetype PDF File size 0.10 MB Source: www.drfoltzemmons.com

ORIGINALCONTRIBUTION

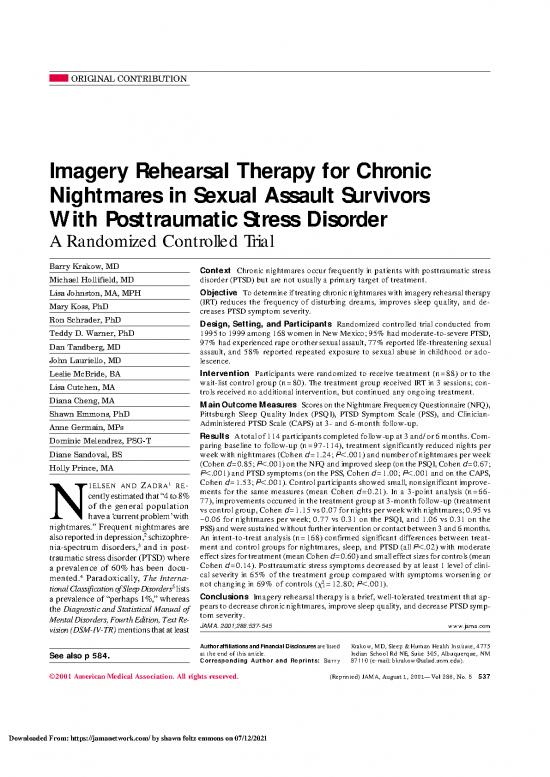

Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for Chronic

Nightmares in Sexual Assault Survivors

With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

A Randomized Controlled Trial

Barry Krakow, MD Context Chronic nightmares occur frequently in patients with posttraumatic stress

Michael Hollifield, MD disorder (PTSD) but are not usually a primary target of treatment.

Lisa Johnston, MA, MPH Objective Todetermineiftreatingchronicnightmareswithimageryrehearsaltherapy

Mary Koss, PhD (IRT) reduces the frequency of disturbing dreams, improves sleep quality, and de-

creases PTSD symptom severity.

RonSchrader, PhD Design, Setting, and Participants Randomized controlled trial conducted from

Teddy D. Warner, PhD 1995to1999among168womeninNewMexico;95%hadmoderate-to-severePTSD,

DanTandberg, MD 97%hadexperiencedrapeorothersexualassault,77%reportedlife-threateningsexual

assault, and 58% reported repeated exposure to sexual abuse in childhood or ado-

John Lauriello, MD lescence.

Leslie McBride, BA Intervention Participants were randomized to receive treatment (n=88) or to the

Lisa Cutchen, MA wait-list control group (n=80). The treatment group received IRT in 3 sessions; con-

trols received no additional intervention, but continued any ongoing treatment.

Diana Cheng, MA MainOutcomeMeasures ScoresontheNightmareFrequencyQuestionnaire(NFQ),

ShawnEmmons,PhD Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), PTSD Symptom Scale (PSS), and Clinician-

Anne Germain, MPs Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) at 3- and 6-month follow-up.

Dominic Melendrez, PSG-T Results Atotalof114participantscompletedfollow-upat3and/or6months.Com-

paring baseline to follow-up (n=97-114), treatment significantly reduced nights per

Diane Sandoval, BS weekwithnightmares(Cohend=1.24;P.001)andnumberofnightmaresperweek

Holly Prince, MA (Cohend=0.85;P.001)ontheNFQandimprovedsleep(onthePSQI,Cohend=0.67;

P.001)andPTSDsymptoms(onthePSS,Cohend=1.00;P.001andontheCAPS,

IELSEN AND ZADRA1 RE- Cohend=1.53;P.001).Controlparticipantsshowedsmall,nonsignificantimprove-

centlyestimatedthat“4to8% ments for the same measures (mean Cohen d=0.21). In a 3-point analysis (n=66-

of the general population 77), improvementsoccurredinthetreatmentgroupat3-monthfollow-up(treatment

Nhavea‘currentproblem’with vscontrolgroup,Cohend=1.15vs0.07fornightsperweekwithnightmares;0.95vs

nightmares.” Frequent nightmares are −0.06 for nightmares per week; 0.77 vs 0.31 on the PSQI, and 1.06 vs 0.31 on the

PSS)andweresustainedwithoutfurtherinterventionorcontactbetween3and6months.

alsoreportedindepression,2schizophre- Anintent-to-treat analysis (n=168) confirmed significant differences between treat-

nia-spectrum disorders,3 and in post- mentandcontrol groups for nightmares, sleep, and PTSD (all P.02) with moderate

traumaticstressdisorder(PTSD)where effectsizesfortreatment(meanCohend=0.60)andsmalleffectsizesforcontrols(mean

a prevalence of 60% has been docu- Cohend=0.14).Posttraumatic stress symptoms decreased by at least 1 level of clini-

4 cal severity in 65% of the treatment group compared with symptoms worsening or

mented. Paradoxically, The Interna- 2 =12.80; P.001).

5 not changing in 69% of controls (1

tionalClassificationofSleepDisorders lists Conclusions Imageryrehearsaltherapyisabrief,well-toleratedtreatmentthatap-

a prevalence of “perhaps 1%,” whereas pearstodecreasechronicnightmares,improvesleepquality,anddecreasePTSDsymp-

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of tomseverity.

MentalDisorders,FourthEdition,TextRe- JAMA.2001;286:537-545 www.jama.com

vision(DSM-IV-TR)mentionsthatatleast

AuthoraffiliationsandFinancialDisclosuresarelisted Krakow, MD,Sleep&HumanHealthInstitute,4775

See also p 584. at the end of this article. Indian School Rd NE, Suite 305, Albuquerque, NM

Corresponding Author and Reprints: Barry 87110 (e-mail: bkrakow@salud.unm.edu).

©2001AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, August 1, 2001—Vol 286, No. 5 537

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by shawn foltz emmons on 07/12/2021

IMAGERYREHEARSALTHERAPY

ports have appeared since25 scription of the study, participants pro-

3%ofyoungadultsreportfrequentnight- ; most nota-

mares,butconcludesthat“actualpreva- bly, Marks26 theorized that rehearsal of vided oral and written consent. Per-

lence of Nightmare Disorder is un- nightmares provides therapeutic ben- sonal interviews and psychometric

6

known.” Thesedisparitiesinprevalence efits through“exposure,abreaction,and instruments were offered to 203 poten-

27 tial participants. At intake, 79% of par-

estimates occur because nightmareepi- mastery,”butBishay suggestedthatex-

demiological research usually surveys posure and abreaction were secondary ticipants were concurrently receiving

disturbingdreamfrequencywithoutin- to mastery because he observed that psychotherapy (primarily counseling)

7-9

quiring about comorbid conditions, changingthestorylineofthedisturbing and/or psychotropic medications (pri-

whereastheDSM-IV-TRstatesthatnight- dream was more effective for the pa- marilytricyclicantidepressantsorselec-

maresoccurringwithanotherpsychiat- tientthanrehearsaloftheoriginaldream. tive serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

ric disorder precludes a nightmare dis- Early in our work with nightmare suf-

6 Randomization and

order diagnosis. This latter and ferers, weobservedthatmasterywaspiv-

prevailing view of disturbing dreams otal in the resolution of chronic night- Blinding Procedures

holds that nightmares are secondary to mares. Kellner et al28 raised the issue of To mask treatment assignment, pa-

another disorder, such as anxiety or whetherIRTwouldbeeffectiveintreat- tients mailed back a postcard after in-

PTSD.5,6,10Whilethisviewhasnosologi- ing severe, chronic nightmares in pa- take to complete entry into the proto-

cal support, it suggests that nightmares tients with comorbid psychiatric disor- col. The postcard’s time and date were

are not a distinctly treatable condition ders, such as PTSD, particularly rape loggedintoacomputerandenteredinto

andthatremissionoccursonlythrough survivors who frequently suffer severe apreviouslygeneratedlistofnumbers

4,29 We also

treatment of the primary disorder. For nightmare disturbances. thatrandomlyassignedparticipantsto

example, if nightmares were attributed speculatedthatsexualassaultsurvivors treatmentandcontrolgroups.Allnum-

to posttraumatic stress, it seems logical mightbereceptivetoIRTbecauseofits bersandgroupassignmentsweregen-

to focus treatment efforts on PTSD, focus on dreams and sleep and its de- eratedatthestartoftheprotocol.Ran-

whichoughttoreducebaddreams,dis- emphasis on exposure to past trau- domizationof168womenproduced2

tress, and impairment.11 matic events. groups: treatment (n=88) and wait-

2

Incontrast,evidenceshowsthatdis- Wetherefore conducted a prospec- list control (n=80) ( =0.38, P=.54)

turbing dreams are associated with tive randomizedcontrolledtrialofIRT (FIGURE1).Of35womenwhodidnot

12-14

psychologicaldistress andsleepim- in a sample predominantly consisting participate,29didnotcompletefullin-

15,16

pairment. Moderate-to-largecorre- of sexual assault survivors with PTSD takepacketsand6didnotreturnpost-

lations between nightmares and anxi- to assess treatment effects of targeted cards.Duetothewait-listdesign,blind-

ety, depression, and PTSD have been nightmare therapy on nightmares, ing was not possible for delivery of

13,14,17

reported. Nightmares disrupt sleep,andposttraumaticstress.Wehy- treatment.Tolimitexternalbias,blind-

sleep, producing conditioning pat- pothesized that sexual assault survi- ingoccurredat3pointsofdatacollec-

terns similar to classic psychophysi- vors treated with IRT would report tion: (1) at intake, group assignment

ological insomnia along with a spe- fewernightmares,improvedsleepqual- had not been established; (2) at

cific complaint of “fear of going to ity, and decreased distress compared 3-month follow-up, questionnaires

12,15,16

sleep.” Prospectivetreatmentstud- with a wait-list control group. werecompletedthroughthemail;and

ies of brief cognitive-behavioral tech- METHODS (3) at 6-month follow-up, interview-

niques, including desensitization and ers were unaware of group status.

imagery rehearsal, which solely tar- Study Population

geted disturbing dreams in nightmare ThestudywasapprovedbytheUniver- Measurements

sufferers without comorbid psychiat- sity of NewMexicoHealthSciencesCen- Primary outcome measures consisted

ric disorders, demonstrated large re- ter institutional review board. Eligible of 5 variables assessed by self-report

ductions in nightmares.18-22 In some participants were female sexual assault withvalidated,standardizedquestion-

studies,decreasednightmareswereas- survivors, 18 years or older, with self- nairescompletedatintakeandfollow-

20,21

sociatedwithdecreasedanxiety and reportednightmares,insomnia,andpost- ups. The Nightmare Frequency Ques-

22

improvementsinsleep. Inaprelimi- traumaticstresssymptomscoupledwith tionnaire (NFQ)assesses“nightswith

6

naryreportonnightmaretreatmentin acriterionAtraumalink. Womenwith nightmares” per unit of time (eg, per

PTSDpatients,disturbingdreamsand acute intoxication, withdrawal, or psy- week,permonth)andactual“number

posttraumatic stress severity de- chosiswereexcluded.Participantswere of nightmares.” Test-retest reliability

creasedandsleepqualityimprovedwith recruited from media efforts (35% of produced weighted of 0.85 to 0.90,

23

imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT). sample),mentalhealththerapistsandfa- and concurrent validity was estab-

24

Wile reportedthefirstcaseseriesin cilities (36%),rapecrisiscenters(17%), lished with a mean correlation coeffi-

whichanimagerytechniquewasusedin andotherresources(10%)from1995to cient of 0.38 (r=0.28-0.49) with mea-

thetreatmentofnightmares.Severalre- 1999. After being given a complete de- sures of anxiety, depression, and

538 JAMA, August 1, 2001—Vol 286, No. 5 (Reprinted) ©2001AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by shawn foltz emmons on 07/12/2021

IMAGERYREHEARSALTHERAPY

17 restructuring paradigm. Treatment as-

PTSD. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Figure 1. Study Flow Chart

Index(PSQI)assessessleepqualityand sumptionsconveyedtothepatientswere

disturbances during the past month asfollows:(1)nightmaresmaybecaused 203 Participants Enrolled

basedon7componentscoresforsleep byuncontrollableandtraumaticevents,

quality, latency, duration, efficiency, yet may serve a beneficial purpose im- 35 Lost to Follow-up

disturbance, medication use, and day- mediately following trauma by provid- 29 Did Not Complete

Intake Packets

time dysfunction that sum to a global inginformationandemotionalprocess- 6 Did Not Return

score (range, 0-21).30 The Clinician- ing;(2)nightmarespersistingformonths Entry Request

AdministeredPTSDScale(CAPS)mea- maynolongerserveusefulpurposesand 168 Randomized

suresfrequencyandintensityofPTSD- maybeviewedmorepragmaticallyasa

related symptoms for the preceding sleep disorder; (3) nightmares may be 80 Assigned to Wait-List 88 Assigned to Cognitive

month (range, 0-136).31 The PTSD successfullycontrolledbytargetingthem Control Group Imagery Treatment

SymptomScale (PSS) measures PTSD ashabitsorlearnedbehaviors;(4)work- Group

symptomsaccordingtoDiagnosticand ing with waking imagery influences 20 Withdrawn 22 Withdrawn Before

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, nightmaresbecausethingsthoughtabout 16 Lost to Follow-up Completing Treatment

Revised Third Edition (DSM-III-R) cri- during the day are related to things 2 Actively Withdrew 15 Lost to Follow-up

2 Moved out of 4 Actively Withdrew

teria to evaluate the severity of intru- dreamedaboutatnight;(5)nightmares State 3 Moved out of State

sion, avoidance, and arousal symp- can be changed into positive, new im- 66 Completed Treatment

toms and sums these scales for total agery; and (6) rehearsing new imagery 60 Completed a 3- and/

or 6-mo Follow-up 12 No Posttreatment

severity in the preceding 2-week pe- (“newdream”)whileawakereducesor 52 Completed 3-mo Follow-up

32 eliminates nightmares, without requir- Follow-up 54 Completed a

riod (range, 0-51). Higher scores re- 53 Completed 6-mo 3- and/or 6-mo

flect greater severity on each measure. ing changes on each and every night- Follow-up Follow-up

Secondarymeasuresincludedthefol- mare. Groups of 4 to 8 women were 44 Completed

3-mo Follow-up

lowing:NightmareEffectsSurvey(NES) formed,andtreatmentwasprovidedon 46 Completed

(impairment associated with night- average every month to every other 6-mo Follow-up

mares),23NightmareDistressQuestion- monthbasedonrecruitment. 60 Included in End Point 54 Included in End Point

naire (NDQ) (distress associated with In the first session of IRT, partici- Analysis Analysis

33 41 Included in 3-Point 36 Included in 3-Point

nightmares), Pittsburgh Sleep Qual- pantsareencouragedtoexamine2con- Analysis Analysis

ity Index-Addendum(PSQI-A)(PTSD- trasting views of nightmares: night- 80 Included in Intent-to- 88 Included in Intent-to-

30 mares as a function only of traumatic Treat Analysis Treat Analysis

related sleep symptoms), Hamilton

AnxietyandDepressionscales,34,35Shee- exposure vs nightmares as a function

han Disability Inventory (SDI) (daily of both traumaandlearnedbehaviors. bothinherwrittenattemptand,ifap-

functioning),36andtheSF-36(physical Participants are asked to explore the plicable,duringtheactualrehearsalpro-

andmentalhealthfunctioning).37Infor- possibility that although nightmares cess. After this initial exercise, partici-

mation was also collected on baseline maybetrauma-induced,theymayalso pantsareencouragedtonotwritedown

historyofpasttraumaticeventsandbase- behabit-sustained.Attheendofthefirst the old nightmare or the changed ver-

line and follow-up use of antidepres- session, participants practice pleasant sion but to establish the process men-

sants,anxiolytic/hypnotics,andconcur- imagery exercises, learn cognitive- tally. They are instructed to rehearse a

rent psychotherapy. The NFQ, PSQI, behavioral tools for dealing with un- newdreamforatleast5to20minutes

andPSSmeasureswereadministeredat pleasantimagesthatmightemerge,and perdaybutnevertoworkonmorethan

3 points in the study; all other mea- are asked to practice pleasant imag- 2 distinct “new dreams” during each

sureswereadministeredatbaselineand ery. At the second session, imagery week.Descriptionsoftraumaticexpe-

6-monthfollow-up. practice is discussed and any difficul- riencesandtraumaticcontentofnight-

ties addressed.Then,participantslearn maresarediscouragedthroughoutthe

Treatment how to use IRT on a single, self- program in a carefully designed at-

Treatment consisted of 3 sessions (two selected nightmare. The participant tempttominimizedirectexposure.To

3-hoursessionsspaced1weekapartwith writesdownherdisturbingdream,then facilitate this approach,participantsare

a1-hourfollow-up3weekslater)using peramodeldevisedbyNeidhardtetal,21 instructed to work first with a night-

a cognitive-imagery treatment,23 pre- is instructedto“changethenightmare mare of lesser intensity and, if pos-

sented in groups (led primarily by B.K. anyway you wish” and to write down sible, onethatdoesnotseemlikea“re-

and a few by L.C. [which were ob- the changed dream. Afterward, each play” or a “reenactment” of a trauma.

served and supervised by B.K.]). The participantusesimagerytorehearseher In3weeks,thegroupmeetsfora1-hour

treatment protocol followed a manual own“newdream”scenariofor10to15 session to discuss progress, share ex-

and focused on nightmares within the minutes.Next,shebrieflydescribesher periences, and ask questions about

frameworkofanimageryandcognitive oldnightmareandhowshechangedit, nightmares, sleep, and PTSD and how

©2001AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, August 1, 2001—Vol 286, No. 5 539

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by shawn foltz emmons on 07/12/2021

IMAGERYREHEARSALTHERAPY

IRT might be useful for other symp- peated measures ANOVAwasthepri- formainoutcomevariableswerefound

toms in addition to nightmares. maryanalyticprocedurereportedinthis (TABLE2).Nosignificantdifferencesbe-

study. Treatment efficacy analyses as- tween groups for concurrent psycho-

Follow-up sessed the following: (1) end point therapyandanxiolytic/hypnoticuseat

Treatment and control participants (n=97-114, changes from baseline to baselineweredetected,butcontrolnon-

weremailedafollow-uppacketofques- endpointbasedonlastfollow-up,3or completers’ concurrent use of antide-

tionnaires at 3 months and invited to 6month,observation carried-forward pressantswassignificantlylessthanuse

apersonalinterviewat6months.Ofthe analysis); (2) 3 points (n=66-77, by other groups at baseline (P=.03)

168randomizedparticipants,96com- changes from baseline to 3-month to (TABLE 3). No significant differences

pleted3-monthfollow-upsbymail,and 6-month follow-up); and, (3) intent- werefoundforfrequencyoftraumatic

99completedthe6-monthfollow-ups to-treat(n=168,changesinbaselineto exposures documented at baseline in-

inperson.Intotal,114individualscom- last observation,includingbaseline,car- terviews (Table 3).

pletedatleast1follow-up,and77par- ried-forward analysis, ie, all random- Eighty-threepercentofparticipants

ticipants completed both follow-ups. ized individuals). reported clinically meaningful post-

Most noncompleters were lost to fol- To test whether moderator vari- traumatic stress severity on the CAPS

low-up early in the program, usually ables influenced treatment effects, re- (score65),31and95%reportedmod-

within1monthofrandomization.How- peated-measures ANOVAs were con- erate or worse posttraumatic stress se-

ever, 12 completedtreatmentsessions ductedonthemainoutcomevariables verity on the PSS (score 11), all of

and then were lost to follow-up (Fig- using each potential moderator as an whommetDSM-III-Rdiagnosticcrite-

ure 1). Contact with control partici- additional between-subjects indepen- ria for PTSD.32Theremaining5%(n=8)

pants was limited to brief telephone dent variable in a treatmenttime experiencedmildposttraumaticstress.

calls and letters to remind them of fu- moderator design. The moderators Nightmare chronicity was not signifi-

tureappointments.Allparticipantswere tested were antidepressant use, anxio- cantly different between the 2 groups

asked to complete a 5-item question- lytic/hypnoticuse,concurrentpsycho- (treatment: mean [SD] of 21.8 [15.3]

naireaboutpotentialsuicidalityatbase- therapy, number of potentially life- years vs control: 19.3 [13.7] years).

line and follow-ups. A few patients re- threatening sexual assaults (“high Ninety percent experienced sexual,

portedacutedistressandwerereferred magnitude”), or repeated exposure to physical, or emotional abuse as chil-

forcrisisintervention.Allcontrolscon- sexual abuse. Repeated measures dren, with sexual abuse the most fre-

tinued any treatment they were al- ANOVAswerealsoconductedonsec- quentlyreported.Fifty-eightpercentre-

readyreceivingandwereofferedtreat- ondarymeasuresbetweenbaselineand ported repeated exposure to sexual

ment at no charge on completion of 6 months. All tests used the .05 level abuseforanaverageperiodof8years,

their 6-month wait-list period. ofsignificanceandeffectsizeswerere- among whom 72% were 10 years old

ported as Cohen d, the standardized or younger when this abuse first oc-

Data Analysis meandifference. curred. Seventy-seven percent re-

Ethnicity, marital status, income, and RESULTS ported high-magnitude sexual as-

educationwereeachcondensedinto2 saults during their lifetime, among

categories due to sparse cells. Com- Demographic and Clinical whom48%experienced2ormoresuch

parison of baseline data on main out- Characteristics events.Threeparticipantswhowereex-

comemeasures for nightmares, sleep, A total of 168 participants were ran- posed to violent, nonsexual assaults

andPTSDanddemographicsfortreat- domized into control and treatment wereretainedintheprotocolandanaly-

mentvscontrolgroupsbycompleters groups and were compared based on sis because their baseline data were

(at end point: completed either 3- or follow-up status: control completers similar to the sexual assault survivors.

6-month follow-up) and noncompl- (n=60),treatmentcompleters(n=54),

eters were analyzed using analysis of control noncompleters (n=20), and Treatment Efficacy

variance (ANOVA) and 2 test. Al- treatment noncompleters (n=34). Treatmenttime interaction effects

thoughpatientswereindividuallyran- Therewasnosignificantdifferencefor were found with a substantial de-

domized, treatment was conducted in lost to follow-up rates between con- crease in nightmares, sleep, and PTSD

smallgroups,andthereforeeffectsmay trol and treatment noncompleters scores at end point for the treatment

have correlated with group member- (Fisher exact test, P=.07). No signifi- group but only small changes, on av-

ship; thus, grouping effects on treat- cantbaselinedifferenceswerefoundbe- erage,forthecontrolgroup(TABLE4).

ment for all main outcome variables tweengroupswiththeexceptionofage Treatment group improvements were

wereinitiallyanalyzedwithrandomef- (P=.01), whereby control noncom- large for nights per week (d=1.24),

38

fects regression usingPROCMIXED pleters were younger than treatment nightmares per week (d=0.85), PSQI

39

in SAS. Because no grouping effects completers (TABLE 1). No significant (d=0.67), PSS (d=1.00), and CAPS

approachedsignificance(allP.90),re- baselinedifferencesamongthe4groups (d=1.53).Forthemainoutcomemea-

540 JAMA, August 1, 2001—Vol 286, No. 5 (Reprinted) ©2001AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by shawn foltz emmons on 07/12/2021

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.