324x Filetype PDF File size 0.97 MB Source: www.cambridge.org

© 2010 George Yule

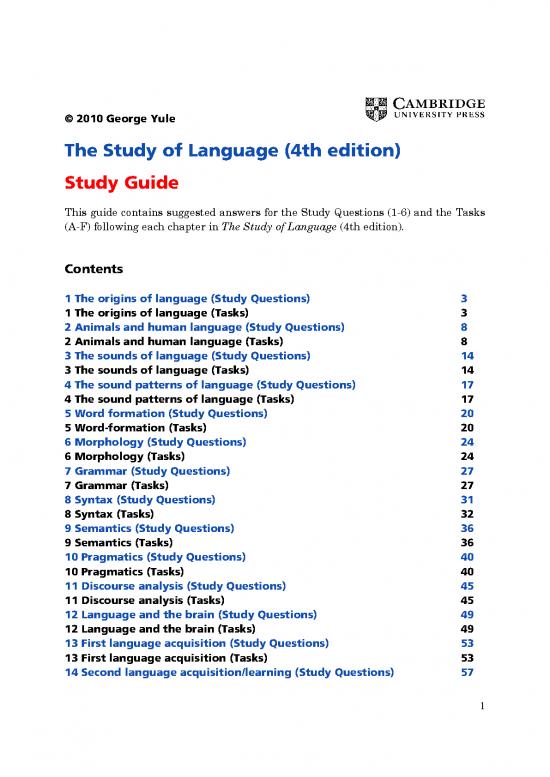

The Study of Language (4th edition)

Study Guide

This guide contains suggested answers for the Study Questions (1-6) and the Tasks

(A-F) following each chapter in The Study of Language (4th edition).

Contents

1 The origins of language (Study Questions) 3

1 The origins of language (Tasks) 3

2 Animals and human language (Study Questions) 8

2 Animals and human language (Tasks) 8

3 The sounds of language (Study Questions) 14

3 The sounds of language (Tasks) 14

4 The sound patterns of language (Study Questions) 17

4 The sound patterns of language (Tasks) 17

5 Word formation (Study Questions) 20

5 Word-formation (Tasks) 20

6 Morphology (Study Questions) 24

6 Morphology (Tasks) 24

7 Grammar (Study Questions) 27

7 Grammar (Tasks) 27

8 Syntax (Study Questions) 31

8 Syntax (Tasks) 32

9 Semantics (Study Questions) 36

9 Semantics (Tasks) 36

10 Pragmatics (Study Questions) 40

10 Pragmatics (Tasks) 40

11 Discourse analysis (Study Questions) 45

11 Discourse analysis (Tasks) 45

12 Language and the brain (Study Questions) 49

12 Language and the brain (Tasks) 49

13 First language acquisition (Study Questions) 53

13 First language acquisition (Tasks) 53

14 Second language acquisition/learning (Study Questions) 57

1

14 Second language acquisition/learning (Tasks) 57

15 Gestures and sign languages (Study Questions) 62

15 Gestures and sign languages (Tasks) 62

16 Writing (Study Questions) 67

16 Writing (Tasks) 67

17 Language history and change (Study Questions) 72

17 Language history and change (Tasks) 72

18 Language and regional variation (Study Questions) 77

18 Language and regional variation (Tasks) 77

19 Language and social variation (Study Questions) 81

19 Language and social variation (Tasks) 81

20 Language and culture (Study Questions) 86

20 Language and culture (Tasks) 86

2

1 The origins of language (Study Questions)

1 First, his conclusion was based on very little evidence and, second, it seems more

reasonable to assume that the children in his study were producing a goat-like

sound from their immediate environment rather than a Phrygian sound from a

distant language.

2 Primitive words could have been imitations of the natural sounds that early

humans heard around them and all modern languages have words that are

onomatopoeic in some way (like “bow-wow”).

3 Interjections contain sounds that are not otherwise used in ordinary speech

production. They are usually produced with sudden intakes of breath, which is the

opposite of ordinary talk, produced on exhaled breath.

4 The pharynx is above the larynx (or the voice box or the vocal folds). When the

larynx moved lower, the pharynx became longer and acted as a resonator,

resulting in increased range and clarity of sounds produced via the larynx.

5 If these deaf children do not develop speech first, then their language ability

would not seem to depend on those physical adaptations of the teeth, larynx, etc.

that are involved in speaking. If all children (including those born deaf) can

acquire language at about the same time, they must be born with a special

capacity to do so. The conclusion is that it must be innate and hence genetically

determined.

6 The physical adaptation source.

1 The origins of language (Tasks)

1A The Heimlich maneuver

The Heimlich maneuver, named after an American doctor, Henry J. Heimlich, is a

procedure used to dislodge pieces of food (or anything else) that are stuck in the

throat, or more specifically, the upper respiratory passage. The procedure is also

known as an abdominal thrust. The danger of getting things stuck in the

respiratory passage, making it difficult or impossible to breathe, is connected to the

lower position of the larynx in humans. The lower larynx is believed to be one of the

keys to the development of human speech and the Heimlich maneuver is a solution

to a life-threatening problem potentially caused by that development.

For more, read:

Crystal, D. (2000) The Cambridge Encyclopedia (512) Cambridge University Press

3

1B The Tower of Babel

According to chapter 11 of the book of Genesis in the Bible, there was a time “when

the whole earth was of one language and of one speech.” The people decided to build

“a tower whose top may reach unto heaven.” God’s reaction to this development was

not favorable:

“And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men

builded. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one

language: and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from

them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound

their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the Lord

scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off

to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did

there confound the language of all the earth. (Genesis 11: 5-9)

The usual interpretation of these events is that humans were united in a single

language and working together to build a tower which represented a challenge to

God, and God intervened in some way so that they couldn’t understand each other

and dispersed them to different places. This can be viewed as an explanation of how

humans started with a single language and ended up with thousands of different,

mutually unintelligible languages all over the world.

Apparently there were many large towers built in Mesopotamia (part of modern

Iraq) which all had names suggesting they were perceived as stairways to heaven.

Robert Dunbar (1996: 152-3) describes one of these towers from a historical point of

view.

“The Tower of Babel was no myth: it really did exist. Its name was Etemenanki

(meaning “the temple of the platform between heaven and earth”), and it was built

some time in the sixth or seventh century BC during the second great flowering of

Babylonian power. It was a seven-stage ziggurat, or stepped pyramid, topped by a

brilliant blue-glazed temple dedicated to the god Marduk, by then the most

powerful of the local Assyrian pantheon. A century or so later, in about 450 BC,

the Greek historian Herodotus struggled up the steep stairways and ramps in the

hope of seeing an idol at the top. Alas, there was nothing but an empty throne.

For more, read:

Dunbar, R. (1996) Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language Harvard

University Press

4

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.