223x Filetype PDF File size 0.29 MB Source: web.econ.ku.dk

Chapter 16

Money in macroeconomics

Moneybuysgoodsandgoodsbuymoney;butgoodsdonotbuygoods.

�Robert W. Clower (1967).

Up to now we have put monetary issues aside. The implicit assumption has

been that the exchange of goods and services in the market economy can be

carried out without friction as mere intra- or intertemporal barter. This is, of

course, not realistic. At best it can provide an acceptable approximation to reality

only for a limited set of macroeconomic issues. We now turn to models in which

there is a demand for money. We thus turn to monetary theory, that is, the study

of causes and consequences of the fact that a large part of the exchange of goods

and services in the real world is mediated through the use of money.

16.1 What is money?

16.1.1 The concept of money

In economics money is de

ned as an asset (a store of value) which functions as a

generally accepted medium of exchange, i.e., it can be used directly to buy any

good o¤ered for sale in the economy. A note of IOU (a bill of exchange) may

also be a medium of exchange, but it is not generally accepted and is therefore

1

not money. Moreover, the extent to which an IOU is acceptable in exchange

depends on the general state in the economy. In contrast, money is characterized

by being a fully liquid asset. An asset is fully liquid if it can be used directly,

instantly, and without any extra costs or restrictions to make payments.

1Generally accepted mediums of exchange are also called means of payment.

645

646 CHAPTER16. MONEYINMACROECONOMICS

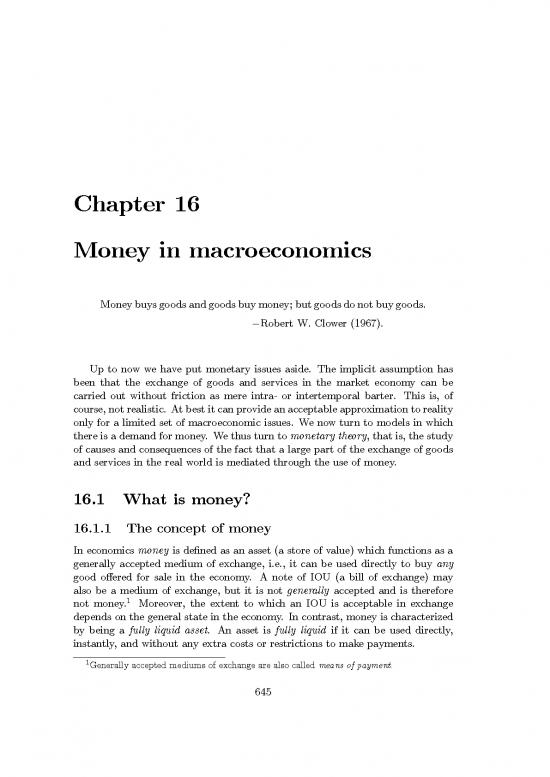

Figure 16.1: No direct exchange possible. A medium of exchange, here good 2, solves

the problem (details in text).

Generally, liquidity should be conceived as a matter of degree so that an asset

has a higher or lower degree of liquidity depending on the extent to which it can

easily be exchanged for money. By easilywe mean immediately, conveniently,

and cheaply. So an assets liquidity is the ease with which the asset can be

converted into money or be used directly for making payments. Where to draw the

line betweenmoneyandnon-moneyassetsdependsonwhatisappropriatefor

the problem at hand. In the list below of di¤erent monetary aggregates (Section

16.2), M corresponds most closely to the traditional de

nition of money. De

ned

1

as currency in circulation plus demand deposits held by the non-bank public in

commercial banks, M embraces all under normal circumstancesfully liquid

1

assets in the hands of the non-bank public.

Thereason that a market economy uses money is that money facilitates trade

enormously, therebyreducingtransactioncosts. Moneyhelpsaneconomytoavoid

the need for a double coincidence of wants. The classical way of illustrating

this is by the exchange triangle in Fig. 16.1. The individuals A, B, and C are

endowed with one unit of the goods 1, 3, and 2, respectively. But A, B, and C

want to consume 3, 2, and 1, respectively. Thus, no direct exchange is possible

between two individuals each wanting to consume the others good. There is

a lack of double coincidence of wants. The problem can be solved by indirect

exchange where A exchanges good 1 for good 2 with C and then, in the next

step, uses good 2 in an exchange for good 3 with B. Here good 2 serves as a

medium of exchange. If good 2 becomes widely used and accepted as a medium

of exchange, it is money. Extending the example to a situation with n goods,

we have that exchange without money (i.e., barter) requires n(n � 1)=2 markets

(trading spots). Exchange with money, in the form of modern paper money,

requires only n markets.

c

Groth, Lecture notes in macroeconomics, (mimeo) 2015.

16.1. What is money? 647

16.1.2 Historical remarks

In the past, ordinary commodities, such as seashells, rice, cocoa, precious metals

etc., served as money. That is, commodities that were easily divisible, handy

to carry, immutable, and involved low costs of storage and transportation could

end up being used as money. This form of money is called commodity money.

Applying ordinary goods as a medium of exchange is costly, however, because

these goods have alternative uses. A more e¢ cient way to trade is by using

currency, i.e., coins and notes in circulation with little or no intrinsic value, or

pieces of paper, checks, representing claims on such currency. Regulation by a

central authority (the state or the central bank) has been of key importance in

bringing about this transition into the modern payment system.

Coins, notes, pieces of paper like checks, and electronic signals from smart

phones to accounts in a bank have no intrinsic value. Yet they may be generally

accepted media of exchange, in which case we refer to them as paper money. By

having these pieces of paper circulating and the real goods moving only once,

from initial producer to

nal consumer, the trading costs in terms of time and

e¤ort are minimized.

In the industrialized countries these paper monies were in the last third of

the nineteenth century and until the outbreak of the First World War backed

through the gold standard. And under the Bretton-Woods agreement, 1947-71,

the currencies of the developed Western countries outside the United States were

convertible into US dollars at a

xed exchange rate (or rather an exchange rate

which is adjustable only under speci

c circumstances); and US dollar reserves

of these countries were (in principle) convertible into gold by the United States

at a

xed price (though in practice with some discouragement from the United

States).

This indirect gold-exchange standard broke down in 1971-73, and nowadays

money in most countries is unbacked paper money (including electronic entries

in banksaccounts). This feature of modern money makes its valuation very

di¤erent from that of other assets. A piece of paper money in a modern payments

system has no worth at all to an individual unless she expects other economic

agents to value it in the next instant. There is an inherent circularity in the

acceptance of money. Hence the viability of such a paper money system is very

much dependent on adequate juridical institutions as well as con

dence in the

ability and willingness of the government and central bank to conduct policies

that sustain the purchasing power of the currency. One elementary juridical

institution is that of legal tender, a status which is conferred to certain kinds

of money. An example is the law that a money debt can always be settled by

currency and a tax always be paid by currency. A medium of exchange whose

market value derives entirely from its legal tender status is called

at money

c

Groth, Lecture notes in macroeconomics, (mimeo) 2015.

648 CHAPTER16. MONEYINMACROECONOMICS

(because the value exists through

at, a rulers declaration). In view of the

absence of intrinsic value, maintaining the exchange value of

at money over

time, that is, avoiding high or uctuating ination, is one of the central tasks of

monetary policy.

16.1.3 The functions of money

The following three functions are sometimes considered to be the de

nitional

characteristics of money:

1. It is a generally accepted medium of exchange.

2. It is a store of value.

3. It serves as a unit of account in which prices are quoted and books kept

(the numeraire).

On can argue, however, that the last function is on a di¤erent footing com-

pared to the two others. Thus, we should make a distinction between the func-

tions that money necessarily performs, according to our de

nition above, and the

functions that money usually performs. Property 1 and 2 certainly belong to the

essential characteristics of money. By its role as a device for making transactions

money helps an economy to avoid the need for a double coincidence of wants.

In order to perform this role, money must be a store of value, i.e., a device that

transfers and maintains value over time. The reason that people are willing to

exchange their goods for pieces of paper is exactly that these can later be used

to purchase other goods. As a store of value, however, money is dominated by

other stores of value such as bonds and shares that pay a higher rate of return.

Whennevertheless there is a demand for money, it is due to the liquidity of this

store of value, that is, its service as a generally accepted medium of exchange.

Property 3, however, is not an indispensable function of money as we have

de

ned it. Though the money unit is usually used as the unit of account in which

prices are quoted, this function of money is conceptually distinct from the other

two functions and has sometimes been distinct in practice. During times of high

ination, foreign currency has been used as a unit of account, whereas the local

money continued to be used as the medium of exchange. During the German

hyperination of 1922-23 US dollars were the unit of account used in parts of the

economy, whereas the mark was the medium of exchange; and during the Russian

hyperination in the middle of the 1990s again US dollars were often the unit of

account, but the rouble was still the medium of exchange.

This is not to say that it is of little importance that money usually serves

as numeraire. Indeed, this function of money plays an important role for the

c

Groth, Lecture notes in macroeconomics, (mimeo) 2015.

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.