224x Filetype PDF File size 0.45 MB Source: msh.org

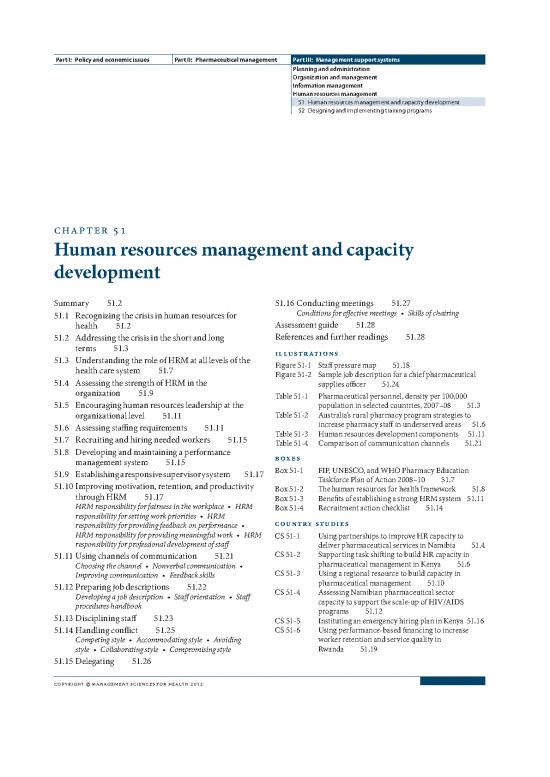

Part I: Policy and economic issues Part II: Pharmaceutical management Part III: Management support systems

Planning and administration

Organization and management

Information management

Human resources management

51 Human resources management and capacity development

52 Designing and implementing training programs

chapter 51

Human resources management and capacity

development

Summary 51.2 51.16 Conducting meetings 51.27

51.1 Recognizing the crisis in human resources for Conditions for effective meetings • Skills of chairing

health 51.2 Assessment guide 51.28

51.2 Addressing the crisis in the short and long References and further readings 51.28

terms 51.3 illustrations

51.3 Understanding the role of HRM at all levels of the Figure 51-1 Staff pressure map 51.18

health care system 51.7 Figure 51-2 Sample job description for a chief pharmaceutical

51.4 Assessing the strength of HRM in the supplies officer 51.24

organization 51.9 Table 51-1 Pharmaceutical personnel, density per 100,000

51.5 Encouraging human resources leadership at the population in selected countries, 2007–08 51.3

organizational level 51.11 Table 51-2 Australia’s rural pharmacy program strategies to

51.6 Assessing staffing requirements 51.11 increase pharmacy staff in underserved areas 51.6

51.7 Recruiting and hiring needed workers 51.15 Table 51-3 Human resources development components 51.11

51.8 Developing and maintaining a performance Table 51-4 Comparison of communication channels 51.21

management system 51.15 boxes

51.9 Establishing a responsive supervisory system 51.17 Box 51-1 FIP, UNESCO, and WHO Pharmacy Education

51.10 Improving motivation, retention, and productivity Taskforce Plan of Action 2008–10 51.7

through HRM 51.17 Box 51-2 The human resources for health framework 51.8

HRM responsibility for fairness in the workplace • HRM Box 51-3 Benefits of establishing a strong HRM system 51.11

responsibility for setting work priorities • HRM Box 51-4 Recruitment action checklist 51.14

responsibility for providing feedback on performance • country studies

HRM responsibility for providing meaningful work • HRM CS 51-1 Using partnerships to improve HR capacity to

responsibility for professional development of staff deliver pharmaceutical services in Namibia 51.4

51.11 Using channels of communication 51.21 CS 51-2 Supporting task shifting to build HR capacity in

Choosing the channel • Nonverbal communication • pharmaceutical management in Kenya 51.6

Improving communication • Feedback skills CS 51-3 Using a regional resource to build capacity in

51.12 Preparing job descriptions 51.22 pharmaceutical management 51.10

Developing a job description • Staff orientation • Staff CS 51-4 Assessing Namibian pharmaceutical sector

procedures handbook capacity to support the scale-up of HIV/AIDS

51.13 Disciplining staff 51.23 programs 51.12

CS 51-5 Instituting an emergency hiring plan in Kenya 51.16

51.14 Handling conflict 51.25 CS 51-6 Using performance-based financing to increase

Competing style • Accommodating style • Avoiding worker retention and service quality in

style • Collaborating style • Compromising style Rwanda 51.19

51.15 Delegating 51.26

copyright management sciences for health 2012

©

51.2 HUMAN RESOURCES MANAgEMENT

suMMary

Human resources are central to planning, managing, Effectively addressing human resources challenges

and delivering health services, including pharmaceutical requires improved leadership and management at all

services. In most countries, personnel account for a high levels. An expanded HRM role, especially at the facility

proportion of the national budget for the health sector— level, is needed to transform the outdated view of human

often 75 percent or more. Despite the critical importance resources as mainly an administrative function to one

of human resources to the functioning of pharmaceuti- where the human resources staff work closely with man-

cal management programs, few concerted efforts have agers to support the health goals of the organization and

addressed the severe staff shortages facing the health to ensure that the right staff with the right skills are in

sector in many countries. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has place to meet these goals.

intensified this already serious situation. Managing people is an important and challenging task for

In addition to staffing shortages, the health system faces any manager. Employees are motivated by many factors

many human resources challenges, including human that can be affected by management. Receiving effective

resources planning, recruitment, deployment, training, supervision, perceiving they are fairly treated, under-

staff motivation, and staff development. The root causes standing their job priorities, getting feedback, feeling

of these issues can be traced to years of neglect, low sala- valued and appreciated, and having opportunities for pro-

ries, poor workplace climate, and limited capacity to train fessional development can all help staff perform better.

and update staff skills. Interventions needed to alleviate Developing and maintaining a fair, equitable, and effec-

the human resources crisis include short-term actions, tive HRM system can motivate staff and increase their

such as task shifting, while in the long term, countries level of job satisfaction and efficiency, which can result

need to expand their capacity to train enough staff to fill in improved service quality. An important part of a

needs. Some issues need to be addressed at the national long-term strategy is creating an organizational and

level (for example, compensation), but many can be management structure for HRM that is implemented by

addressed through better leadership and human resource managers and staff at all levels. A human resources part-

management (HRM) at the facility level. In the pharma- nership between senior managers, supervisors, human

ceutical sector, the goal of HRM is to develop and sustain resources professionals, and individual staff members is

an adequate supply of skilled professionals who are moti- what makes an HRM system work.

vated to provide a high level of pharmaceutical care.

51.1 Recognizing the crisis in human deliver effective services. In these countries, staff attrition

resources for health rates are rising because of HIV infection, illness, and death

as well as the migration of staff to urban areas or other coun-

Countries throughout the world, especially developing tries. Vacancy rates in public-sector organizations are also

countries, have long suffered from a severe lack of skilled rising, while the pool of skilled candidates to fill positions is

health workers and managers. The delivery of health ser- still not deep enough. Results from a twelve-country survey

vices is labor intensive, and the workforce is the primary showed that the problem is so serious that countries simply

determinant of health system effectiveness, yet strategies do not have the human resources capacity to absorb, deploy,

and systems for human capacity development in most min- and use additional funds that they are receiving to improve

istries of health are inadequate to meet the needs of the health (Kinfu et al. 2009). Estimates cited in the survey indi-

population. In addition, the lack of health staff, including cate that workforces in the most-affected countries would

trained pharmacy staff, has compromised health care in need to increase by up to 140 percent to attain health devel-

rural areas. Moreover, the demands of scaling up antiret- opment targets.

roviral treatment (ART) programs and the related time- The pharmaceutical personnel situation in many coun-

consuming care have overburdened already weak systems tries is dire; for example, countries such as Benin and

for human resources development and management and Mali have less than one pharmaceutical worker for every

drained personnel from other health services. Absenteeism 100,000 people, whereas France, in comparison, has more

and low morale are widespread, and work-related stress than 100 per 100,000 (Table 51-1). Uganda has an esti-

reduces health workers’ productivity. mated 30 percent of the pharmacists it actually needs

Countries with a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS that can- (Matsiko and Kiwanuka 2003). Some industrialized coun-

not address acute shortages in the short term are unable to tries also have pharmacy staff shortages; many areas of the

51 / Human resources management and capacity development 51.3

a

Table 51-1 Pharmaceutical personnel, density per For example, in Kenya, 58 percent of health facilities are

100,000 population in selected countries, 2007–08 in the public sector, whereas 86 percent of the pharma-

Country Density ceutical workforce is employed in the private sector (FIP

2009). Country Study 51-1 shows how a public-private

Benin < 1 partnership in Namibia, where pharmacists prefer

Niger < 1 private-sector employment, successfully recruited and

Senegal 1 pharmacy professionals into public-sector service.

Burkina Faso 2 Poor distribution of staff: The predominance of health work-

Malawi 2 ers is in urban areas—where they earn more and have

access to better opportunities—meaning that rural areas

Uzbekistan 3 often suffer from acute shortages of trained workers.

Bhutan 4 Uganda is a country that has less than one pharmacist

Ghana 7 per 100,000 people in its population, but almost 90 per-

Liberia 8 cent of the existing pharmacists are located in the Central

Nigeria 13 region, while the other 10 percent are divided among the

other four regions in the country (FIP 2006).

Turkey 33 Insufficient preservice training: Many countries lack the

Albania 39 ability to train enough pharmaceutical professionals to

Israel 76 fill their needs; they may have no or only one accredited

Bahrain 86 school of pharmacy, for example. Increasing the number

France 118 of skilled workers requires capacity in the educational

Source: WHO Department of Human Resources for Health 2008. system—enough teachers, updated curriculum, and

a adequate infrastructure—which takes time to build. Even

Pharmaceutical personnel include pharmacists, pharmaceutical technicians, and when graduates are available, retention is difficult unless

pharmaceutical technologists.

good management exists to absorb, train, and support

them.

United States have some difficulty filling pharmacist posi-

tions (FIP 2009).

The dynamics of entry and exit from the health workforce 51.2 Addressing the crisis in the short and

in many countries remains poorly understood, and many long terms

reasons—such as lack of investment in training, illness,

and premature retirement and death—contribute to the global action is required not only to address high-priority

shortage. This lack of understanding inhibits countries and infectious diseases but also to meet the long-term human

development partners from developing and implementing resources needs of health systems in developing countries.

appropriate interventions. Several factors, however, are rec- The greatest challenge is to begin addressing shortages of

ognized as important contributors to the shortage of trained health personnel in an integrated and comprehensive fash-

pharmacy personnel and other health care workers, includ- ion. Responses to the challenge must meet both the short-

ing— term necessities of providing lifesaving treatment and the

long-term human resources needs of the health sector (see

Migration of health personnel: Migration contributes signifi- Country Study 51-1).

cantly to the loss of health workers from many countries. Short-term responses include implementing aggressive

For example, almost two-thirds of ghana’s 140 pharmacy retention policies, such as improving terms and conditions

school graduates in 2003 migrated to a different country; of service for health workers, providing ART to health work-

between 2001 and 2004, Zimbabwe had about 150 new ers who need it to preserve their health and productivity,

pharmacy graduates, while 100 Zimbabwean pharma- and encouraging temporary regional migration of work-

cists registered to work in the United Kingdom during ers from countries with surplus workers to countries with

the same period (FIP 2006). Even relatively well-off deficits. For example, Kenya has bilateral agreements with

countries like South Africa are losing trained health pro- Namibia, Southern Sudan, and Lesotho to send nurses to

fessionals to richer economies (FIP 2006). work on short-term contracts in those countries.

Staff leaving the public sector: Health staff members leave Task shifting has been used extensively and often effec-

the public sector to work for donor-funded projects tively to fill gaps in health care worker shortages, includ-

that are flourishing from the large influx of money into ing in pharmacies (WHO Maximizing Positive Synergies

Africa; in addition, health workers often choose to work Collaborative group 2009). Often, lower-level pharmacy

in the private sector, where remuneration is often better. workers, such as pharmacy technicians, or other cadres,

51.4 HUMAN RESOURCES MANAgEMENT

Country study 51-1

using partnerships to improve human resources capacity to deliver pharmaceutical services in Namibia

Human resources crisis in pharmacy • RPM Plus worked with the MoHSS to develop a

According to the World Health Organization’s global mechanism to expedite the hire of pharmacists and

Atlas of the Health Workforce, in 2004, Namibia had pharmacist assistants for priority positions in the

fourteen pharmacists per 100,000 people, or half of South public sector; all target positions were identified and

Africa’s twenty-eight pharmacists per 100,000. Namibia’s aligned with MoHSS priorities.

pharmacists are also poorly distributed—80 percent • Job descriptions for temporary staff were made

work in the private sector, leaving priority public health commensurate with those in the public sector; work

programs short of qualified staff. About half the pharma- standards were set according to MoHSS policies.

cists working in the public sector are located in Khomas • The MoHSS led the interview and selection process.

region, particularly in Windhoek city, leaving the other • Remuneration for recruited staff was set in accor-

twelve regions short of qualified personnel. Pharmacist dance with the MoHSS scale.

assistants in most district hospitals occupy positions • A local human resources company, Potentia

meant for more highly skilled pharmacists. Namibia Recruitment Consultancy, recruited suc-

cessful personnel and managed their remuneration

In 2006, of the forty-eight public-sector pharmacy posts and benefits.

available, only fourteen were filled—four of these were • The MoHSS directly supervised and evaluated the

filled by Namibians. performance of recruited personnel.

Challenges in filling positions in Namibia • The MoHSS mobilized its own resources and sys-

tems to progressively absorb the newly appointed

• Foreigners on two-to-three-year contracts fill 90 personnel into the government personnel structure.

percent of pharmacist positions. Knowledge of local Results of the partnership

languages is critical; English speakers usually need

translators to communicate with patients, while the In two years, twenty-eight pharmaceutical staff members

many Cuban pharmacists have a hard time because (eleven pharmacists, one network administrator, and six-

of a lack of Spanish translators. teen pharmacy assistants) were recruited; 64 percent of

• No pharmacy school exists in Namibia, and an the staff positions have been absorbed into the public ser-

inadequate number of Namibian students pursue a vice (46 percent of the pharmacists and 81 percent of the

pharmacy degree abroad. Those who do return from pharmacy assistants). Despite Namibia’s lucrative private

abroad choose careers in the private sector. sector, no pharmacist that the partnership recruited and

• Of 515 students pursuing health and social wel- supported has been lost to the private sector. Vacancy

fare training at the University of Namibia during rates have been reduced by more than half, and evidence

2003–04, only two were enrolled in the prepharmacy suggests that the quality of pharmaceutical care and ser-

program. vices has improved. According to the Kunene regional

• The Namibia National Health Training Center director, “There is better ordering of pharmaceutical

trained only about eight pharmacist assistants in a items and stock management has improved. The com-

year. pilation of consumption pattern has been done, and it is

• The public-sector recruitment process was time con- easier to forecast needs of certain pharmaceutical items.

suming; therefore, engaging pharmacists—particu- The Regional and District Therapeutic Committees have

larly those from abroad—took a long time. been resuscitated and have begun to look more closely at

A partnership to expedite the recruitment of pharmaceutical issues in the region and districts.”

pharmacy staff Lessons learned

The Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS) and The time and resources needed to manage staff before

the Rational Pharmaceutical Management Plus (RPM they were absorbed into the public sector proved higher

Plus) Program developed an intervention with the goal than RPM Plus expected. Thus, contracting with a local

of increasing the number of facilities with qualified phar- human resources company to manage the seconded staff

maceutical staff. The partnership model comprised the on behalf of the MoHSS and RPM Plus proved vital to the

following components— partnership’s success. Additional steps that were critical

to the process included working closely with the MoHSS

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.