208x Filetype PDF File size 2.36 MB Source: sph.unc.edu

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY VOL.66,NO.14,2015

ª 2015 BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION ISSN 0735-1097/$36.00

PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER INC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.050

THEPRESENTANDFUTURE

STATE-OF-THE-ARTREVIEW

Food Consumption and its Impact

on Cardiovascular Disease:

Importance of Solutions Focused on

the Globalized Food System

AReport From the Workshop Convened by the

World Heart Federation

Sonia S. Anand, MD, PHD,*y Corinna Hawkes, PHD,z Russell J. de Souza, SCD, RD,x Andrew Mente, PHD,y

Mahshid Dehghan, PHD,y Rachel Nugent, PHD,k Michael A. Zulyniak, PHD,* Tony Weis, PHD,{

AdamM.Bernstein, MD,# Ronald M. Krauss, MD,** Daan Kromhout, MPH, PHD,yy

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PHD, DSC,zzxx Vasanti Malik, SCD,kk Miguel A. Martinez-Gonzalez, MPH, MD, PHD,{{

Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DRPH,## Salim Yusuf, MD, DPHIL,y Walter C. Willett, MD, DRPH,{{ Barry M. Popkin, PHD***

ABSTRACT

Major scholars in the field, on the basis of a 3-day consensus, created an in-depth review of current knowledge on the

role of diet in cardiovascular disease (CVD), the changing global food system and global dietary patterns, and potential

policy solutions. Evidence from different countries and age/race/ethnicity/socioeconomic groups suggesting the health

effects studies of foods, macronutrients, and dietary patterns on CVD appear to be far more consistent though regional

knowledge gaps are highlighted. Large gaps in knowledge about the association of macronutrients to CVD in low-

and middle-income countries particularly linked with dietary patterns are reviewed. Our understanding of foods and

macronutrients in relationship to CVD is broadly clear; however, major gaps exist both in dietary pattern research and

ways to change diets and food systems. On the basis of the current evidence, the traditional Mediterranean-type diet,

including plant foods and emphasis on plant protein sources provides a well-tested healthy dietary pattern to reduce

CVD. (J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1590–614) © 2015 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

From the *Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; yPopulation Health Research Institute,

HamiltonHealthSciencesandMcMasterUniversity,Hamilton,Ontario,Canada;zCentreforFoodPolicy,CityUniversity,London,

United Kingdom; xDepartment of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada;

kDepartmentofGlobalHealth,UniversityofWashington,Seattle,Washington;{DepartmentofGeography,UniversityofWestern

Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada; #Center for Lifestyle Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Lyndhurst, Ohio; **Children’s Hospital

Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California; yyDivision of Human Nutrition, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the

Netherlands; zzDepartment of Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada;

xxClinical Nutrition & Risk Factor Modification Center, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; kkDepartment of

Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts; {{Departamento de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Publica,

Universidad de Navarra-CIBEROBN, Pamplona,Spain; ##Friedman School of Nutrition Science & Policy, Tufts University, Boston,

Massachusetts; and the ***Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Car-

olina.Dr.deSouzahasservedasanexternalresourcepersonontransandsaturatedfatstotheWorldHealthOrganization’sNutrition

GuidelinesAdvisoryGroup.Dr.BernsteinbeganworkingatRallyHealthinApril2015.Dr.Krausshasreceivedgrantsupportfromthe

U.S.NationalDairyCouncil,theDairyResearchInstitute,theAlmondBoardofCalifornia,andQuestDiagnostics;andhasservedasa

consultant for Quest Diagnostics. Dr. Jenkins has served on the scientific advisory boards of Unilever, Sanitarium Company, Cali-

fornia Strawberry Commission,LoblawSupermarket,HerbalLifeInternational,NutritionalFundamentalforHealth,PacificHealth

Laboratories, Metagenics, Bayer Consumer Care, Orafti, Dean Foods, Kellogg’s, Quaker Oats, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, NuVal

GriffinHospital,Abbott,PulseCanada,SaskatchewanPulseGrowers,andtheCanolaCouncilofCanada;hasreceivedhonorariafor

scientificadvicefromtheAlmondBoardofCalifornia,theInternationalTreeNutCouncilNutritionResearchandEducationFoundation,

JACC VOL. 66, NO. 14, 2015 Anand et al. 1591

OCTOBER 6, 2015:1590–614 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

here is much controversy surrounding the increasing global attention to the importance ABBREVIATIONS

optimal diet for cardiovascular health. Data of improving food systems by the interna- ANDACRONYMS

Trelating diet to cardiovascular diseases tional developmentandnutritioncommunity

(CVDs) has predominantly been generated from (9–11). Although the “food system” may seem CHD=coronary heart disease

high-income countries (HIC), but >80% of CVD remotetoacliniciansittinginanofficeseeing CI = confidence interval

deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries a patient, its impact on the individuals they CVD=cardiovascular disease

(LMIC). Relatively sparse data on diet and CVD exist aretryingtotreatareveryreal.Thispaperison GI = glycemic index

from these countries though new data sources are the basis of a World Heart Federation inter- GL=glycemic load

rapidly emerging (1,2). Noncommunicable diseases national workshop to review the state of HDL-C = high-density

are forecasted to increase substantially in LMIC knowledge on this topic. This review of diet, lipoprotein cholesterol

because of lifestyle transitions associated with in- dietarypatterns,andCVDisnotonthebasisof HIC = high-income countries

creasing urbanization, economic development, and newsystematicreviewsormeta-analysesbut LDL-C = low-density

globalization. The Global Burden of Disease study representsacarefulreviewofmanypublished lipoprotein cholesterol

cites diet as a major factor behind the rise in hyper- meta-analyses, seminal primary studies, and LMIC = low- and middle-

tension, diabetes, obesity, and other CVD compo- recent research by the scholars who partici- income countries

nents (3). There are an estimated >500 million patedintheConsensusconference. MI = myocardial infarction

obese (4,5) and close to 2 billion overweight or obese This paper presents: 1) an overview of the OR=oddsratio

individuals worldwide (6). Furthermore, unhealthy development of the modern, globalized food RCT=randomized controlled

dietary patterns have negative environmental im- system and its implications for the food trial

pacts, notably on climate change. supply; 2) a consensus on the evidence RR=relative risk

Poor quality diets are high in refined grains and relating various macronutrients and foods to SSB=sugar-sweetened

beverage

added sugars, salt, unhealthy fats, and animal-source CVD and its related comorbidities; and 3) an

foods; and low in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, outline of how changes to the global food T2DM=type2diabetes

mellitus

legumes, fish,andnuts.Theyareoftenhighinpro- system can address current diet-related pub-

cessed food products—typically packaged and often lic health problems, and simultaneously have bene-

readytoconsume—andlightonwholefoodsandfreshly ficial impacts on climate change.

prepared dishes. These unhealthy diets are facilitated

by modern food environments, a problem that is THECHANGINGFOODSYSTEMAND

likely to become more widespread as food environ- FOODSUPPLYANDIMPLICATIONSFOR

ments in LMIC shift to resemble those of HIC (5,7,8). DIETSANDTHEENVIRONMENT

In this paper, we summarize the evidence relating

food to CVD, and the powerful forces that underpin THEDEVELOPMENTOFTHEMODERN,GLOBALIZED

the creation of modern food environments—what we FOOD SYSTEM. Food systems were once dominated

call the global food system—to emphasize the impor- bylocalproductionforlocalmarkets,withrelatively

tanceofidentifyingsystemicsolutionstodiet-related little processing before foods reached the household

health outcomes. We do this in the context of (OnlineAppendix,Box1)(12).Incontrast,themodern

Barilla, Unilever Canada, Solae, Oldways, Kellogg’s, Quaker Oats, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, NuVal Griffin Hospital, Abbott, the

Canola Council of Canada, Dean Foods, the California Strawberry Commission, Haine Celestial, and the Alpro Foundation; has

served on the speakers panel for the Almond Board of California; has received research grant support from Loblaw Brands Ltd,

Unilever, Barilla, the Almond Board of California, Solae, Haine Celestial, Sanitarium Company, Orafti, the International Tree Nut

Council, and the Peanut Institute; has received travel support to attend meetings from the Almond Board of California, Unilever,

theAlproFoundation,theInternationalTreeNutCouncil,theCanadianInstitutesforHealthResearch,theCanadaFoundationfor

Innovation, and the Ontario Research Fund; has received salary support as a Canada Research Chair from the federal government

of Canada; and discloses that his wife is a director of Glycemic Index Laboratories, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Martinez-

Gonzalez has had a research contract with Danone to support research on yogurt in the SUN cohort; and received a depart-

mental grant from the International Nut Council. Dr. Mozaffarian has served on the scientific advisory board of Unilever North

America; received ad hoc honoraria from Bunge and the Haas Avocado Board; received consulting fees from Nutrition Impact,

Amarin, AstraZeneca, Life Sciences Research Organization, and Boston Heart Diagnostics; and receives royalties for an online

chapter on fish oil entitled “Fish Oil and Marine Omega-3 Fatty Acids.” Dr. Popkin has received funding to speak on sugar-

sweetened beverages (SSB) behaviors globally from Danone water research center at 2 international conferences in the past 5

years; and was a coinvestigator to a water versus SSB randomized controlled trial funded by Danone to the Mexican National

Institute of Public Health in Cuernavaca, Mexico. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the

contents of this paper to disclose. Drs. Anand and Hawkes contributed equally to this work.

Listen to this manuscript’s audio summary by JACC Editor-in-Chief Dr. Valentin Fuster.

Manuscript received May 5, 2015; revised manuscript received July 16, 2015, accepted July 20, 2015.

1592 Anand et al. JACC VOL. 66, NO. 14, 2015

Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System OCTOBER 6, 2015:1590–614

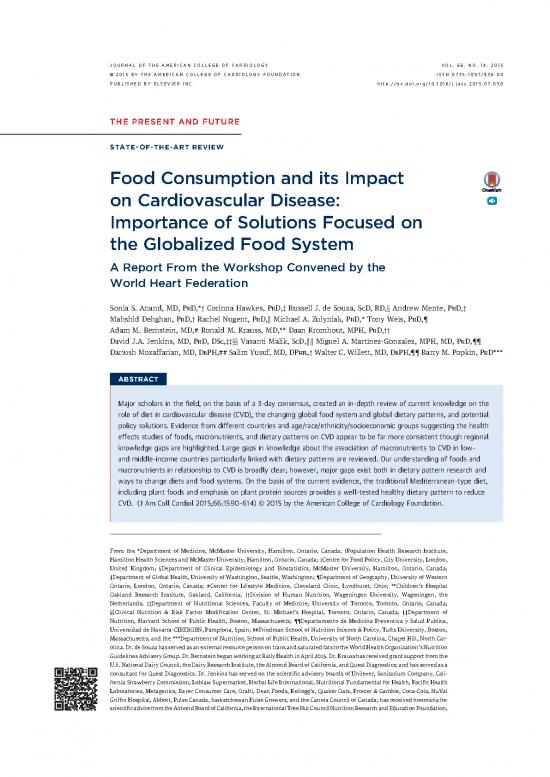

FIGURE1 FoodSystemImpactonNutrition-Related NCDs

Food Food Intermediate Nutrition Nutrition Health

system system factor consumption outcomes outcomes

drivers factors

Public sector Retailers Price and Quantity Balanced Wellness

institutions availability diet

Agriculture Packaged Under/over NCD

sector food sector Diversity nutrition vulnerability

development

Climate Agrochemical-seeds/ Nutrient Ecosystem

change/ Agro-processing Quality deficiencies health

Biodiversity loss

Street food/fast

food/restaurant

sector

Source: revised version of Nugent, 2011 ”Bringing Agriculture to the Table“ Chicago Council on Global Affairs. NCD ¼ noncommunicable disease.

food system is characterized by a global web of in- (e.g., wheat, corn, rice) cheaply available, in order to

teractions between multiple actors from farm to fork, simultaneously address hunger in LMIC and national

geared toward maximizing efficiency to reduce costs food insecurity in HIC (23). In addition to vastly

and increase production (Figure 1). The major actors increasing the calorie supply, the ensuing produc-

whocontrolthissystemhavechangeddramaticallyin tivity boom also provided the basis of cheap feed for

HIC and LMIC, as described subsequently (13). livestock and cheap inputs for processed foods, in

The shift to a global food system started in the turn creating incentives for the growth of manufac-

United States and other high-income industrialized turers of processed foods (24). This coincided with

countries, and was driven initially by government huge technological innovations in food processing,

investment and intervention in markets, infrastruc- (24–28), the rise of mass marketing to persuade con-

ture and research intended to raise farm-sector pro- sumers to eat more, supermarket retailing, and fast

ductivity. Building on actions taken in the late 19th food (29,30). As a result of these changes, the trans-

century (14), policies on agricultural research and formation of raw commodities into food and the dis-

supporting on-farm production introduced in the tribution of consumable food items beyond the farm

periodfrom1930to1960intheUnitedStates(14)and gate has become far more important (31). Today,

Europe focused on few major crops, particularly integration and control of our farm-to-fork food

grains (e.g., wheat, corn, rice), oilseeds (e.g., soy- supply by major agribusinesses, food manufacturers,

beans), livestock (e.g., pigs, poultry, cattle), and retailers, and food service companies is more the rule

critical cash crops, especially sugar cane and other than the exception (13). Meanwhile, production of

sources of sugar (15–18). State intervention in most less processed foods such as coarse grains (e.g., mil-

LMIC took a different form, such as policies to sub- let, sorghum), roots, tubers, and legumes has

sidize food, taxes on agricultural products, and sys- declined (32,33) whereas animal source food produc-

tems to control the supply and marketing of key tion has grown dramatically (34).

commodities (19–22). The 1960s also saw the start of Figure 2 sets out the stages of change involved in

significant agricultural transformation in LMIC, with leading to this modern food system. This model has

the “Green Revolution,” which focused on increasing spread unevenly to most LMIC (35–37). Many coun-

productivity of corn, rice, and wheat. tries retain various forms of state intervention in

These investments and changes in production agriculture and food systems (18,38–41), but policies

systems were designed to make calories from staples to liberalize trade and private sector investment have

JACC VOL. 66, NO. 14, 2015 Anand et al. 1593

OCTOBER 6, 2015:1590–614 Diet, Cardiovascular Disease, and the Food System

FIGURE2 Stages of Global Agricultural System Development

Scientific and technological change, economic change, urbanization, globalization

Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 Stage 6

1800s mainly 1900-1944 Post-WWII massive Systematically Commercial sector Healthier food

scientific investments modern transmitted globally shifts major drivers of supply

underpinnings system (1955-2008) system change

(present)

Create the modern Retailers,agricultural

Expansion food system focused Farm research, input & processing, Price incentives,

Science and technologies; on staples, animal extension systems, businesses, and food taxation, and system

institution building science source foods, and cash and education mirror manufacturers investments

crops those of the West dominate farm-level

decision-making

Fossil energy, Extensive funding for Investment training, Food industry farm links

modern genetics, major infrastructure, institutions, drive production and

fertilizer, beginning Expansion of science; systems, input and infrastructure, marketing decisions, Investments in

agriculture science develop reaper; many enhanced seeds, and CGIARC (consoritum incentives and infrastructure and

and experimental other technologies major technology global international economic drivers training

work, & land grant/ development agricultural research) change

agriculture universities

High income

Farming systems countries see rapid Reduced

developed; mechanization; Green revolution, Production linked to noncommunicable

Farming remains the underpinnings post- development of new irrigation, credit, farm the needs of food diseases, reduced

major source of the WWII revolution food processing extension, and manufacturers and climate footprint,

food supply; added modernization technologies (e.g. agricultural institutions retailers, ignoring achieve total

Industrial/large-scale of agricultural extraction of edible mirror those of the climate, sustainability, sustainability, fewer

monoculture initiated production inputs and oils from oil seeds); west; modernizing of and health concerns animal source foods

machinery and investment in food processing consumed

transportation/

irrigation/

electrification/

modernization of

agriculture

Source: ª (copyright) Barry M. Popkin, 2015.

revolutionized the entire sector in many regions carbohydrates—refined grains and added sugars.

(13,42). Retailing has been transformed in LMIC Rapidlyincreasingproductionofstarchystaplescom-

through the growth of supermarkets (18,38–41). binedwithprocessingtechnologiesmeanthatrefined

Although this process originated with companies in flourisincreasinglydominantindiets.Whitebread,for

industrialized countries looking for growth in foreign example, once rarely consumed in Latin America,

markets, companies based in LMIC are now also became widespread after the introduction of high-

investing back into HIC. yield wheat varieties. In Asia, white rice became

DIETARY IMPACTS. Thewaypeopleeathaschanged dominant as a staple over legumes and coarse grains,

greatlyacrosstheglobe;moreover,thepaceofchange with a more recent trend being rapidly rising con-

inLMICisquickening.Snackingandsnackfoodshave sumption of instant noodles as a staple (52,53).

growninfrequencyandnumber(43–48); eating fre- Since1964,averagetotalcarbohydrateintakein

quencyhasincreased;away-from-homeeatinginres- theUnitedStateshasincreasedfromabout375g/dayto

taurants,infastfoodoutlets,andfromtake-outmeals 500g/day(from2to6kg/yearofready-to-eatcereals),

is increasing dramatically in LMIC; both at home and but the percent of carbohydrate that is fiber has

away-from-home eating increasingly involves fried not substantially changed over this time, reflecting

andprocessedfood(47,49);andtheoverallproportion increasedrefinedcarbohydratesandsugar-sweetened

ofhighlyprocessedfoodindietshasgrown(50,51). beverages(SSBs)ishighinHIC(54).In the period from

These changes in the global food system coupled 1985 to 2005 extensive added sugar intake occurred

with these food behavior shifts have enabled some across HIC (55) but more recently large increases

critical changes to the global food supply, all with have occurred in LMIC, particularly in consumption

dietary implications. First is the shift to refined of SSBs and processed foods (56–59). Today in the

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.