183x Filetype PDF File size 0.16 MB Source: jamanetwork.com

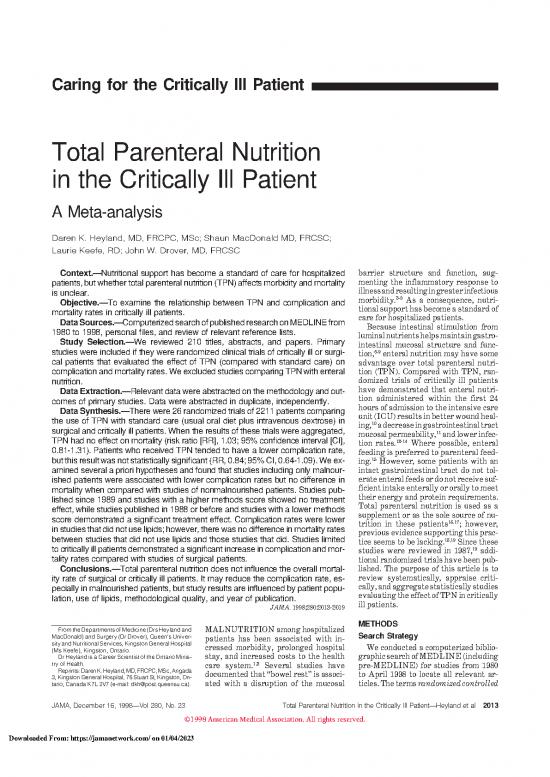

Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

Total Parenteral Nutrition

in the Critically Ill Patient

AMeta-analysis

Daren K. Heyland, MD, FRCPC, MSc; Shaun MacDonald MD, FRCSC;

Laurie Keefe, RD; John W. Drover, MD, FRCSC

Context.—Nutritional support has become a standard of care for hospitalized barrier structure and function, aug-

patients, but whether total parenteral nutrition (TPN) affects morbidity and mortality menting the inflammatory response to

is unclear. illnessandresultingingreaterinfectious

Objective.—To examine the relationship between TPN and complication and morbidity.3-5 As a consequence, nutri-

mortality rates in critically ill patients. tional supporthasbecomeastandardof

DataSources.—ComputerizedsearchofpublishedresearchonMEDLINEfrom care for hospitalized patients.

1980 to 1998, personal files, and review of relevant reference lists. Because intestinal stimulation from

Study Selection.—We reviewed 210 titles, abstracts, and papers. Primary luminalnutrientshelpsmaintaingastro-

intestinal mucosal structure and func-

studies were included if they were randomized clinical trials of critically ill or surgi- tion,6-9 enteral nutrition may have some

cal patients that evaluated the effect of TPN (compared with standard care) on advantage over total parenteral nutri-

complicationandmortalityrates.WeexcludedstudiescomparingTPNwithenteral tion (TPN). Compared with TPN, ran-

nutrition. domized trials of critically ill patients

DataExtraction.—Relevantdatawereabstractedonthemethodologyandout- have demonstrated that enteral nutri-

comes of primary studies. Data were abstracted in duplicate, independently. tion administered within the first 24

DataSynthesis.—Therewere26randomizedtrialsof2211patientscomparing hoursofadmissiontotheintensivecare

the use of TPN with standard care (usual oral diet plus intravenous dextrose) in unit(ICU)resultsinbetterwoundheal-

10

surgical and critically ill patients. When the results of these trials were aggregated, ing, adecreaseingastrointestinaltract

11

mucosalpermeability, andlowerinfec-

TPNhadnoeffectonmortality (risk ratio [RR], 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 12-14

0.81-1.31). Patients who received TPN tended to have a lower complication rate, tion rates. Where possible, enteral

feeding is preferred to parenteral feed-

butthisresultwasnotstatisticallysignificant(RR,0.84;95%CI,0.64-1.09).Weex- 15

ing. However, some patients with an

aminedseveralapriori hypotheses and found that studies including only malnour- intact gastrointestinal tract do not tol-

ished patients were associated with lower complication rates but no difference in erateenteralfeedsordonotreceivesuf-

mortality when compared with studies of nonmalnourished patients. Studies pub- ficientintakeenterallyororallytomeet

lished since 1989 and studies with a higher methods score showed no treatment their energy and protein requirements.

effect, while studies published in 1988 or before and studies with a lower methods Total parenteral nutrition is used as a

score demonstrated a significant treatment effect. Complication rates were lower supplement or as the sole source of nu-

trition in these patients16,17

in studies that did not use lipids; however, there was no difference in mortality rates ; however,

previousevidencesupportingthisprac-

between studies that did not use lipids and those studies that did. Studies limited tice seems to be lacking.18,19 Since these

to critically ill patients demonstrated a significant increase in complication and mor- 19

tality rates compared with studies of surgical patients. studies were reviewed in 1987, addi-

tional randomizedtrialshavebeenpub-

Conclusions.—Total parenteral nutrition does not influence the overall mortal- lished. The purpose of this article is to

ity rate of surgical or critically ill patients. It may reduce the complication rate, es- review systematically, appraise criti-

pecially in malnourished patients, but study results are influenced by patient popu- cally,andaggregatestatisticallystudies

lation, use of lipids, methodological quality, and year of publication. evaluatingtheeffectofTPNincritically

JAMA.1998;280:2013-2019 ill patients.

FromtheDepartmentsofMedicine(DrsHeylandand MALNUTRITIONamonghospitalized METHODS

MacDonald)andSurgery(DrDrover),Queen’sUniver- patients has been associated with in- Search Strategy

sityandNutritionalServices,KingstonGeneralHospital creased morbidity, prolonged hospital Weconductedacomputerizedbiblio-

(Ms Keefe), Kingston, Ontario. graphicsearchofMEDLINE(including

DrHeylandisaCareerScientistoftheOntarioMinis- stay, and increased costs to the health

try of Health. care system.1,2 Several studies have pre-MEDLINE) for studies from 1980

Reprints:DarenK.Heyland,MD,FRCPC,MSc,Angada documentedthat“bowelrest”isassoci- to April 1998 to locate all relevant ar-

3, KingstonGeneralHospital,76StuartSt,Kingston,On- ated with a disruption of the mucosal ticles.Thetermsrandomizedcontrolled

tario, Canada K7L 2V7 (e-mail: dkh@post.queensu.ca).

JAMA, December 16, 1998—Vol 280, No. 23 Total Parenteral Nutrition in the Critically Ill Patient—Heyland et al 2013

©1998AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 01/04/2023

Table 1.—Criteria Used to Assess Methodologic Quality* blinding the administration of TPN, we

Score only awarded points for studies that

blinded the adjudication of study end

012

points. We also evaluated the extent to

Randomization . . . Not concealed Concealed randomization which consecutive, eligible patients

or not sure were enrolled in the trial, whether

Blinding Not blinded . . . Adjudicators blinded groupswereequalatbaseline,ifcointer-

Analysis Other . . . Intention to treat ventions were adequately described,

Patient selection Selected patients or Consecutive eligible ... whether objective definitions of infec-

unable to tell patients tious outcomeswereused,andwhether

Comparability of groups No or not sure Yes . . . all patientswereproperlyaccountedfor

at baseline

Extent of follow-up ,100% 100% . . . intheanalysis(intention-to-treatanaly-

Treatment protocol Poorly described Reproducibly described . . . sis) (Table 1).

Cointerventions† Not described Described but not equal Well described and

or not sure all equal Data Extraction

Outcomes Not described Partially described Objectively defined Twoofus(D.K.H.andS.M.)extracted

*The first 3 questions and the last 2 questions had a possible score of 0, 1, or 2. The middle 3 questions had a data for analysis and assessment of the

possible score of 0 or 1. The highest possible score was 14. Ellipses indicate data not applicable. methodologic quality; we resolved dis-

†Theextenttowhichantibiotics,enteralnutrition,ventilation,oxygen,andtransfusionswereappliedequallyacross agreementbyconsensus.Notallstudies

groups. reportedcomplicationrates.Somestud-

trial,doubleblindmethod,clinicaltrial, differences that might exist between ies reported total complications per

placebo, and comparative study were thesepatientsinthesubgroupanalysis. group but not on a per-patient basis.

combined with explode parenteral nu- Weexcludedstudiesofpediatricorneo- Whendataweremissing,unclear,ornot

trition, total. Citations were limited to natal patients. reported on a per-patient basis, we at-

English-language studies reporting on Weincluded only studies that evalu- temptedtocontacttheprimaryinvesti-

adult patients. Reference lists of rel- atedtheuseofsupplementalTPNinpa- gators and requested them to provide

evant review articles and personal files tientsreceivingenteralfeedsorstudies further information if the article had

werealsosearched. evaluating the use of TPN in patients beenpublishedinthelast5years.

Study Selection Criteria whowerenotreceivingTPNorenteral Prior Hypotheses Regarding Sources

nutrition.Thereareseveralrandomized of Heterogeneity

Initially, 2 of us (D.K.H. and S.M.) trials of surgical patients that examine

screenedallcitationsandclassifiedthem theeffectofaminoacidinfusion(without When conducting a systematic re-

as primary studies, review articles, or additional nonprotein energy or lipids) view, heterogeneity (major differences

other. We then retrieved and reviewed onclinicaloutcomes.Suchtherapyisnot in the apparent effect of the interven-

independently all primary studies. Pri- astandardofcareinthecriticallyillpa- tions across studies) is often found.

marystudieswereselectedforinclusion tient,whereasTPN(withorwithoutlip- Whenheterogeneityispresent,itweak-

in this overview if the study’s (1) re- ids) is commonly administered to criti- ensinferencesthatcanbemadefromthe

searchdesignwasarandomizedclinical callyill patients. Forthepurposeofthis results. The possible sources of varia-

trial; (2) populationconsistedofsurgical review, we excluded studies that used tion in study results include the role of

orcritically ill human adult subjects; (3) only amino acid infusions as the inter- chance or differences across studies in

intervention included any form of TPN vention.Asthescopeofourreviewwas population, intervention, outcome, and

(protein, source of nonprotein energy definedbyourresearchquestion,wealso methods.Wedevelopedseveralhypoth-

with or without lipids) compared with excluded studies that compared TPN esesthatmightexplainheterogeneityof

standardcare(oraldietplusintravenous with enteral nutrition or other forms of studyresults.

fluids); and (4) outcome measures in- TPN.Finally,studiesthatevaluatedthe First,weconsideredthatthepremor-

cludedcomplications,lengthofstay,and impact of TPN only on nutritional out- bid nutritional status of study patients

mortality. comes (ie, nitrogen balance, amino acid was a possible cause of variation in re-

Becausestudiesinwhichtreatmentis profile)werenotincludedinthisarticle. sults. Where possible, we grouped the

allocated in any method other than ran- Whiletheseendpointsmayexplainun- results of studies that included only pa-

domizationtendtoshowlarger(andfre- derlying pathophysiology, we consid- tientswhoweremalnourishedandcom-

quentlyfalse-positive)treatmenteffects eredtheseassurrogateendpoints23and pared them with the results of studies

than do randomized trials,20 we elected weonly included articles that reported thatincludedpatientswhowerenotmal-

to include only randomized trials in this on clinically important outcomes (mor- nourished at entrance into the study.

review.Wedefinedcriticallyillpatients bidity and mortality). Whenpossible,weusedthedefinitionof

as those who would routinely be cared Methodologic Quality malnourishedprovidedineachstudy.If

for in a critical care environment. Pa- of Primary Studies nonewasprovided,weassumedpatients

tients undergoing major surgery may whohadgreaterthan10%weightlossto

notalwaysbecaredforinacriticalcare Weassessedthemethodologicquality bemalnourished.

environment but share similarities in ofallselectedarticlesinduplicate,inde- Second, we hypothesized that study

their response to illness, a hypercata- pendently, using a scoring system that results may be related to the methodo-

bolicstatecharacterizedbyweightloss, we have used previously24 (Table 1). logic quality of the study. We planned a

loss of body fat, and accelerated break- Eveninrandomizedtrials,failuretopre- separate analysis comparing the effect

down of body proteins.21 Previous sys- vent foreknowledge of treatment as- of studies with an overall methodologic

tematicreviewshaveincorporateddata signmentcanleadtoanoverestimation quality score to those with a score less

from surgical patients and critically ill of treatment effect.25 Accordingly, we than7(medianscore,7).

15,22 Third, since the practice of providing

patients. Therefore,weoptedtocom- scored higher those studies that re-

bine studies of surgical patients and portedthattheirrandomizationschema nutritional support and managing criti-

critically ill patients and to explore any was concealed. Given the difficulties of cally ill patients has evolved over time

2014 JAMA,December16,1998—Vol280,No.23 Total Parenteral Nutrition in the Critically Ill Patient—Heyland et al

©1998AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 01/04/2023

(included studies range from 1976 to withbiasandinstabilityassociatedwith Tobetterunderstandourfindings,we

1997), we divided the studies into equal RRestimationinsparsedata,weadded proceeded to examine our a priori hy-

groups comparing studies published in onehalftoeachcell.35Inthemeta-analy- potheses. We compared trials that in-

1988 or earlier with studies published sis, we used maximum likelihood meth- cludedonlymalnourishedpatientswith

since 1989 (halfway point of the study odsofcombiningRRacrossalltrialsand other trials. No difference in mortality

range). examined the data for evidence of het- existed(Figure3)forstudiesofmalnour-

36

Fourth, since some studies adminis- erogeneitywithingroups. TheMantel- ished patients (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.75-

tered amino acids and a carbohydrate Haenszel37 method was used to test the 1.71) or in studies that included ad-

source of energy while others adminis- significanceoftreatmenteffect.Weused equately nourished patients (RR, 1.00;

tered amino acids, carbohydrates, and a random effects model to estimate the 95%CI,0.71-1.39;P=.64fordifferences

lipids,weseparatedtrialsintothosethat overallRR.38,39Forthetestofheteroge- between subgroups). The rate of major

included lipids and those without. We neity across subgroups, we used the t complications was significantly lower

hypothesizedthattheremaybeadverse testforthedifferencebetweenthe2sub- amongmalnourishedpatientsreceiving

26

effects caused by lipid use. groups.WeconsideredP,.05tobesta- TPN(RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30-0.91). No

Finally, we speculated that differ- tistically significant. difference existed in complication rates

encesinpatientpopulations(surgicalvs amongstudies of adequately nourished

critically ill) may account for different RESULTS patients (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.75-1.40).

results. To test this hypothesis, we Study Identification and Selection Thedifferenceincomplicationratesbe-

planned a separate analysis comparing tween these subgroups was of border-

studiesofsurgicalpatientswithstudies Atotalof153citationswereidentified line significance (P=.05).

of critically ill patients. through a computerized bibliographic Wecomparedtrials with a methodo-

Analysis database search. Our personal files and logicqualityscoreoflessthan7withtri-

review of reference lists yielded 57 ad- alswithascoreof7orbetter(Figure3).

The primary outcome was periopera- ditionalarticlesforconsideration.Initial Trials with the higher methods score

tivemortality(deathwithin30daysofop- eligibility screening resulted in 46 ar- demonstratednoeffectofTPNonmor-

eration) or mortality reported at dis- ticles selectedforfurtherevaluation.Of tality (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.88-1.56). We

charge from hospital. The secondary thesepotentiallyeligiblestudies,26met noted a trend toward a lower mortality

outcomewastherateofmajorcomplica- the inclusion criteria. rate in studies with a lower methods

tions.Wedefinedmajorcomplicationsas Wereached100%agreementonthein- score (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.49-1.19). The

pneumonia,intra-abdominalabscess,sep- clusion of articles for this systematic re- difference between these 2 subgroups

sis,linesepsis,myocardialinfarction,pul- view.Reasonsforexcludingrelevantran- was short of conventional levels of sig-

monaryemboli,heartfailure, stroke, re- domized studies included studies not nificance (P=.12). Withrespecttocom-

generalizable to critically ill patients40

nalfailure, liver failure, and anastomotic ; plication rates, studies with a higher

leak.Minorcomplicationsweredefinedas studies that evaluated different kinds of methods score demonstrated no treat-

woundinfection, phlebitis, urinary tract TPN41-43;studiesthatevaluatedaminoac- menteffect(RR,1.13;95%CI,0.86-1.50).

infection,andatelectasis.In4studies,the ids only44-47; pseudorandomized studies Studies with a lower methods score

datawerenotportrayedinafashionthat (not true randomization)48-52; studies du- showed a significant reduction in com-

allowed us to report major complication plicated in other publications34,53,54; stud- plication rates associated with TPN

rates, so we reported total compli- iesnotreportingclinicallyimportantout- (RR,0.54;95%CI,0.33-0.87).Thediffer-

27-29 55-57 enceincomplicationratesbetweenthese

cations and total infectious complica- comes ; studies available in abstract

tions.30 Reporting methods of individual formonly58;andastudythatalsorandom- subgroupswassignificant (P=.02).

studies did not allow us to disaggregate ized patients to anabolic steroids.59 Wenextcomparedtrialspublishedin

infectious from noninfectious complica- 1988 or earlier with trials published in

tions.Onestudy31randomizedpatientsto Impact of TPN on Mortality 1989orlater(Figure3).Trialspublished

3 groups (control vs standard TPN vs and Complications Rates in 1988 or earlier demonstrated a trend

TPNwithbranch-chainaminoacids).We Thereare26randomizedtrialsinvolv- towardalowermortalityrateassociated

onlyincludeddatafromthecontrolgroup ing2211patientsthatcomparetheuseof withTPN(RR,0.70;95%CI,0.44-1.13).

andthestandardTPNgroup.Twoother TPNwithstandard care (usual oral diet Trials published since 1989 demon-

studies randomized patients to 3 groups plusintravenousfluids)inpatientsunder- strated no treatment effect (RR, 1.18;

(control vs TPN without lipids vs TPN going surgery,27-34,60-74 patients with pan- 95%CI,0.89-1.57).Differencesbetween

withlipids),andweincludedbothexperi- creatitis,75 patients in an intensive care these2subgroupswereshortofconven-

mental groups in the analysis.32-34 One unit,76 and patients with severe burns.77 tional levels of statistical significance

study included reports of 2 trials.34 The The details of each study, including the (P=.07).Thereweresignificantlyfewer

secondtrialwaspresumedtoincludepa- methodologicqualityscore,aredescribed major complications associated with

tients from the first trial and was there- inTable2.Whentheresultsofthesetrials TPNreportedinstudiesthatwerepub-

foreexcluded.Wealsoreportedondura- wereaggregated, there was no effect on lished in 1988 or earlier (RR, 0.49; 95%

tionofhospitalstay,althoughthesedata mortality (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.81-1.31) CI,0.29-0.81),whileinstudiespublished

were not aggregated because of infre- (Figure1).Thetestforheterogeneitywas since1989therewasnoeffectofTPNon

quentandvariablereportingmethods. notsignificant(P=.59),althoughavisual complication rates (RR, 1.19; 95% CI,

Agreementbetweenreviewersonin- inspection of Figure 1 suggests that the 0.93-1.53).ThePvalueforthedifference

clusion of articles was measured by k treatmenteffects are variable. between these subgroups was signifi-

withquadratic weights. Twenty-two studies reported major cant (P=.005).

Wecombineddatafromallstudiesto complications in study patients. Aggre- Wethen compared studies that pro-

estimate the common relative risk of gation of these results revealed a trend videdintravenouslipidsasacomponent

mortality and complications and associ- toward reducing complication rates in ofTPNadministrationwithstudiesthat

ated95%confidenceintervals(CIs).We patients receiving TPN (RR, 0.84; 95% did not include lipids. In studies that

summarized the treatment effect using CI,0.64-1.09)(Figure2).Thetestforhet- usedlipids(RR,1.03;95%CI,0.78-1.36)

risk ratios (RRs). To avoid the problem erogeneity was significant (P=.003). and studies that did not (RR, 0.98; 95%

JAMA, December 16, 1998—Vol 280, No. 23 Total Parenteral Nutrition in the Critically Ill Patient—Heyland et al 2015

©1998AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 01/04/2023

Table 2.—Randomized Studies Evaluating Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) in Critically Ill Patients*

%of

Methods Malnourished

Source, y Score Patient Population (No.) Patients Intervention

27

Veterans Affairs, 1991 10 Thoracoabdominal surgery (395) 100 TPNwith lipids 14 d before surgery

28

Fan et al, 1989 10 Esophageal cancer surgery (40) 75 TPNwith lipids 7-15 d before surgery

29

Figueras et al, 1988 7 Gastrointestinal surgery (49) 0 TPNwithout lipids after surgery

30

Sandstrom et al, 1993 10 Major surgery/trauma (300) 22 TPNwith lipids after surgery

31

Reilly et al, 1990 7 Liver transplant (18) 100 TPNwith lipids after surgery

32

Hwang et al, 1993a§ 5 Gastric surgery (42) . . . TPNwith lipids after surgery

32

Hwang et al, 1993b§ 5 Gastric surgery (42) . . . TPNwithout lipids after surgery

33

Muller et al, 1982 3 Gastrointestinal surgery (125) 60 TPNwithout lipids 10 d before surgery

34

Muller et al, 1986 4 Gastrointestinal surgery (105) . . . TPNwith lipids 10 d before surgery

60

Jimenez et al, 1986 5 Gastrointestinal surgery (75) 100 TPNwithout lipids after surgery

61

Brennan et al, 1994 8 Pancreatic resection (117) . . . TPNwith lipids after surgery

62

Askanazi et al, 1986 3 Radical cystectomy (35) . . . TPNwith lipids after surgery

63

Thompson et al, 1981 4 Gastrointestinal surgery (21) 100 TPNwithout lipids 5 d before surgery

64

Fan et al, 1994 7 Hepatocellular cancer surgery (124) 26 TPNwith lipids 7 d before surgery

65

Abel et al, 1976 4 Cardiac surgery (44) 100 TPNwithout lipids after surgery

66

Bellatone et al, 1988 6 Gastrointestinal surgery (100) 100 TPNwith lipids 7 d before surgery

67

Smith and Hartemink, 1988 7 Gastrointestinal surgery (34) 100 TPNwithout lipids 10 d before surgery

Holter and Fischer,68 1977 5 Gastrointestinal surgery (56) 100 TPNwithout lipids 3 d before surgery

69

Meguid et al, 1988 4 Gastrointestinal surgery (64) 100 TPNwith lipids 9 d before surgery

70

Woolfson and Smith, 1989 10 Thoracoabdominal surgery (122) . . . TPNwith lipids after surgery

71

Von Meyenfeldt et al, 1992 7 Gastrointestinal surgery (101) 29 TPNwith lipids 10 d before surgery

72

Yamada et al, 1983 3 Gastric surgery (62) . . . TPNwith lipids after surgery

73

Gys et al, 1990 7 Colorectal surgery (20) 0 TPNwith lipids after surgery

74

Freund et al, 1979 8 Gastrointestinal surgery (35) 0 TPNwithout lipids after surgery

75

Sax et al, 1987 8 Pancreatitis (54) . . . TPNwith lipids after admission

76

Chiarelli et al, 1996 6 Neurology ICU (24) . . . TPNafter admission; both groups received EN

(unknown lipids)

77 1989 7 Burns on .50% of body (49) . . . TPNwithout lipids after admission; both groups

Herndon et al,

received EN

*Ellipses indicate data not available; EN, enteral nutrition; ICU, intensive care unit.

†Presented as mean ± SD or (range).

‡No range was specified.

§Control group is the same for both criteria.

CI,0.49-1.95),therewasnodifferencein

mortality.(Pvalueforthedifferencebe- 65 Holter and Fischer,68 1977

Abel et al, 1976

68 74

tween subgroups=.89). Complication Holter and Fischer, 1977 Freund et al, 1979

74 63

rates in studies that used lipids demon- Freund et al, 1979 Thompson et al, 1981

63 33

Thompson et al, 1981 Muller et al, 1982

33 72

stratednoeffect(RR,0.96;95%CI,0.69- Muller et al, 1982 Yamada et al, 1983

72 Brennan et al,61 1994

Yamada et al, 1983

1.34). In studies that did not use lipids, 61 62

Brennan et al, 1994 Askanazi et al, 1986

62 34

the complication rate was significantly Askanazi et al, 1986 Muller et al, 1986

34 75

Muller et al, 1986 Sax et al, 1987

lower(RR,0.59;95%CI,0.38-0.90).The 75 66

Sax et al, 1987 Bellatone et al, 1988

66 67

Pvalueforthedifferencebetweenthese Bellatone et al, 1988 Smith and Hartemink, 1988

69 28

Meguid et al, 1988 Fan et al, 1989

subgroupswasjustshortofsignificance 67 29

Smith and Hartemink, 1988 Figueras et al, 1988

28 70

(P=.09). Fan et al, 1989 Woolfson and Smith, 1989

29 73

Figueras et al, 1988 Gys et al, 1990

77 27

Finally, we compared studies of criti- Herndon et al, 1989 Veterans Affairs, 1991

70 71

callyillpatientswithstudiesofprimarily Woolfson and Smith, 1989 Von Meyenfeldt et al, 1992

73 32

Gys et al, 1990 Hwang et al, 1993a

31 32

surgical patients. The mortality rate of Reilly et al, 1990 Hwang et al, 1993b

27 64

critically ill patients was higher among Veterans Affairs, 1991 Fan et al, 1994

71 60

Von Meyenfeldt et al, 1992 Jimenez et al, 1995

32 76

those receiving TPN (RR, 1.78; 95% CI, Hwang et al, 1993a Chiarelli et al, 1996

32

1.11-2.85), while studies of surgical pa- Hwang et al, 1993b

30 Overall Risk Ratio

Sandstrom et al, 1993

64

tients showed no treatment effect (RR, Fan et al, 1994 0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

Jimenez et al,60 1995

0.91;95%CI,0.68-1.21).Thedifferencebe- 76

Chiarelli et al, 1996 TPN TPN

tweenthese subgroups was statistically Overall Risk Ratio Beneficial Harmful

significant(P=.03).Thecomplicationrates 0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100 Risk Ratio (Log Scale)

inthestudiesofcriticallyillpatients(only TPN TPN

2 studies reported complication rates) Beneficial Harmful Figure 2.—Risk ratios and associated 95% confi-

showedatrendtowardanincreaseincom- Risk Ratio (Log Scale) dence intervals for the effect of total parenteral nu-

plications (RR, 2.40; 95% CI, 0.88-6.58), trition (TPN) on major complications.

whilestudiesofsurgicalpatientswereas- Figure 1.—Risk ratios and associated 95% confi-

sociated with lower complication rates denceintervalsforeffectoftotalparenteralnutrition

(RR,0.76;95%CI,0.48-1.0).ThePvalue (TPN) on mortality.

for the difference between these sub- the variability in duration of stay and

groupswassignificant(P=.05). ported median stay and 9 reported variabilityofreportingmethods,wedid

Only14studiesreportedtheeffectof means.In8studies,thedurationofstay notstatisticallyaggregatetheseresults,

TPNonduration of hospital stay; 5 re- wasshorterinthecontrolgroup.Dueto buttheyaredisplayedinTable2.

2016 JAMA,December16,1998—Vol280,No.23 Total Parenteral Nutrition in the Critically Ill Patient—Heyland et al

©1998AmericanMedicalAssociation. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 01/04/2023

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.